The Terracotta Army forms part of the vast mausoleum of Qin Shi Huang, the First Emperor of China, and stands as one of the most extraordinary archaeological testaments to imperial power, military organization, and beliefs about the afterlife in ancient China.

In the spring of 1974, peasants digging a well outside modern Xi’an stumbled upon fragments of terracotta figures of extraordinary craftsmanship. This accidental discovery has since been recognized as one of the most remarkable archaeological finds of the 20th century: a vast underground tomb complex guarded by an army of individualized, life-sized terracotta soldiers. These warriors were created to protect the tomb of Qin Shi Huang (259-210 BC), the First Emperor of China, in the afterlife. His burial complex, located at the foot of Mount Li – the traditional burial ground of Qin rulers – was conceived on a monumental scale comparable to that of an imperial capital. The mausoleum offers an unparalleled insight into military might, systems of governance, technological sophistication, and deeply held funerary beliefs of the newly unified Qin empire. Although Qin Shi Huang failed in his quest for physical immortality, the mausoleum stands as a powerful testament to his ambition to continue ruling in a parallel world beyond death. Accordingly, he recreated beneath the earth the empire he had forged above it.

Construction of the mausoleum began shortly after Qin Shi Huang ascended to the throne and continued for nearly four decades, yet the immense project remained unfinished at the time of his death. The undertaking was overseen by the imperial chancellor and administered through a hierarchy of high-ranking officials who supervised its various stages and specialized workshops. According to historical sources, more than 700,000 laborers – the majority of them prisoners, convicts, and conscripted workers – were mobilized for its construction. Following the conquest of the rival states of the Warring States period – Chu, Qi, Yan, Han, Zhao, and Wei – large numbers of people from subjugated territories were forcibly relocated to contribute their labor and technical skills, underscoring the extraordinary scale of imperial ambition and state control. Conceived as an underground city for the afterlife, the tomb complex was designed to mirror the political and cosmic order of the Qin empire. At its center lies the emperor’s burial mound, which remains unexcavated, largely due to concerns about preservation and safety. Over the past five decades, however, Chinese archaeologists have identified approximately 600 subsidiary tombs and burial pits surrounding it, including those housing the Terracotta Army, as well as storage facilities, stables, workshops, and burial grounds for individuals associated with the emperor or the construction of the complex.

“As soon as the First Emperor became king of Qin, excavations and building had been started at Mount Li, while after he won the empire, more than é conscripts from all parts of the country worked there. They dug through three underground streams and poured molten copper for the outer coffin, and the tomb was filled with models of palaces, pavilions and offices as well as fine vessels, precious stones and rarities. Craftsmen were ordered to fix up crossbows so that any thief breaking in would be shot. All the country’s streams, the Yellow River and the Yangtze were reproduced in mercury and by some mechanical means made to flow into a miniature ocean. The heavenly constellations were above and the regions of the earth below. The candles were made of man-fish oil to ensure them burning for the longest possible time.”

Sima Qian: Records of the Grand Historian [Shi Ji] (109-91 BC)

The mausoleum complex is oriented eastward, a direction traditionally associated with renewal and authority, and the emperor’s tomb is enclosed by two massive rammed-earth walls. The inner wall measures approximately 3,870 meters in length, while the outer wall extends about 6,322 meters. Together, these walls form two concentric rectangular enclosures – an inner and an outer city – that replicate the spatial organization of an imperial capital. Moreover, their configuration evokes the shape of a Chinese written character, underscoring the symbolic and cosmological significance embedded in the mausoleum’s design. The inner city contains the emperor’s burial mound, the underground palace, and associated ceremonial and residential structures, reinforcing the belief that imperial life would continue after death. At the northeastern corner of the inner city lies the cemetery of the concubines, where the skeletal remains of young women were discovered alongside gold and pearl ornaments, indicating their high status within the court. Nearby, pits containing imperial chariots further emphasize the expectation that the emperor would continue to travel and govern in the afterlife as he had in life.

One of the most celebrated discovers is the Pit of the Imperial Chariots, located west of the burial mound. Here, archaeologists uncovered two half-scale bronze chariots from Qin Shi Huang’s ceremonial procession, complete with horses and drivers. These vehicle rank among the most valuable and technically sophisticated finds within the entire mausoleum complex, representing the pinnacle of ancient Chinese bronze-working. Over the centuries, the immense weight of the overlying earth crushed the ensemble, shattering it into thousands of fragments. As a result, archaeologists chose to remove the remains from their original location in large wooden crates that enclosed both the chariots and the surrounding mass of earth. This was followed by a painstaking process of cleaning, conservation, and reassembly – a task that took eight years to complete. Far from being merely symbolic objects, the chariots are precise technical models, complete with functioning components such as axles, suspension systems, and reins, reflecting both the ceremonial splendor of the imperial court and the advanced technological knowledge of the Qin period.

The outer city contained support facilities essential to sustaining the imperial household beyond death, including repositories for documents, stables, armories, treasuries, storage pits, and the living quarters of palace staff. This area also included the burial grounds of those who entertained the emperor, as well as those of his favorite animals. Among the most striking finds is the Pit of the Stone Armor, situated on the eastern side of the outer city, where archaeologists recovered 90 suits of armor and 43 helmets. These objects were assembled from meticulously cut and finely polished green limestone plaques, bound with copper wires in a manner that closely imitates the construction of real armor made from leather and iron. The craftsmanship is extraordinary: each suit of armor consists of 612 stone plaques of varying sizes and weighs approximately 20 kilograms, while each helmet is composed of 74 plaques and weighs about 3.8 kilograms. Although precise in form and structure, these armors were never intended for actual combat. Their considerable weight and inherent fragility indicate that they were created exclusively as funerary objects, intended to provide symbolic protection for the emperor and his retinue against malevolent spirits in the afterlife.

Adjacent to this pit lies the Pit of the Entertainers, which offers a rare glimpse into refined leisure at the Qin imperial court. This pit contained terracotta figures of acrobats, dancers, and musicians. In contrast to the rigid, military poses of the terracotta warriors, the acrobats are animated and captured in the midst of performance. A group of terracotta musicians is depicted playing various instruments alongside bronze representations of waterfowl. In designing this setting, considerable attention was paid to recreating a convincing aquatic environment. Within the long, tunnel-like trench, bronze swans, wild geese, and cranes were placed on narrow wooden planks along both sides, with their heads turned toward the center, thereby simulating the banks of a body of water. Excavations have recovered a total of 20 swans, 20 wild geese, and 6 cranes from the trench. No two birds are exactly alike, subtle variations in posture, proportion, and surface detail create a dynamic and lifelike scene. This attention to individualization, even in the representation of animals, underscores the Qin artisans’ exceptional skill in bronze casting and reflects a broader belief that the pleasures and diversions of imperial life should continue unbroken in the afterlife.

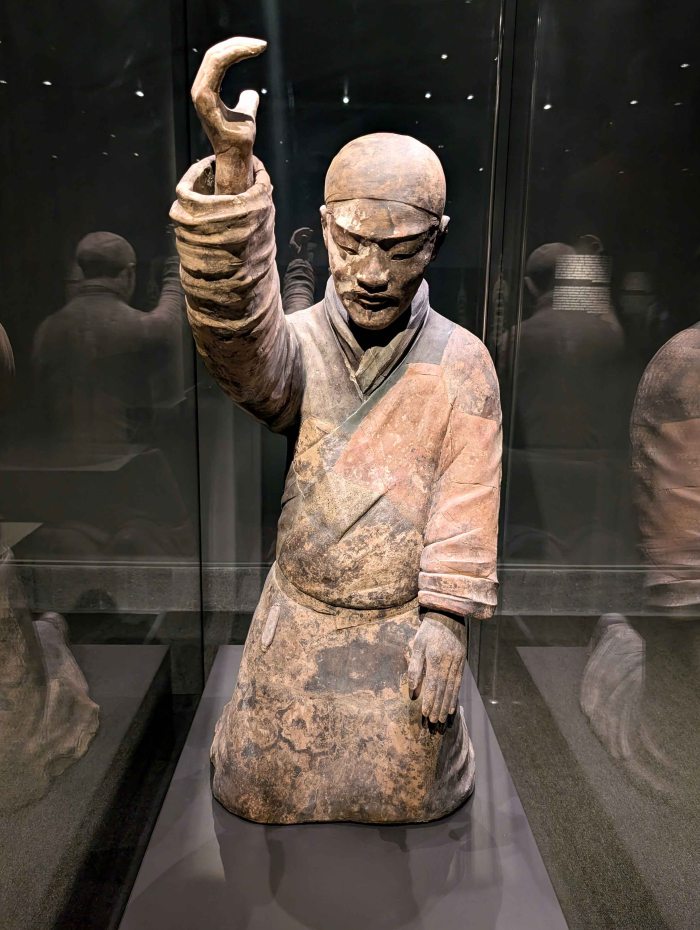

The third group of finds lies outside the city and comprises a wide range of specialized burial areas. The most famous and visually striking component of the tomb complex is the Terracotta Army, housed in three major archaeological pits located approximately 1.5 kilometers east of the central burial mound. Of the four pits that have been excavated, three contain figures, while one remains empty. These pits are strategically positioned to symbolize the military defense of the imperial capital. The Imperial Stables have also been excavated; here, real horses were buried alongside finely modelled terracotta figures of kneeling grooms, ready to take the emperor hunting or to war as occasion demanded. To the north are large storage complexes for documents and artifacts, as well as a garden for rare birds. On the western side are stone-working workshops, tile-firing kilns, and the cemetery of the laborers who constructed the mausoleum, starkly illustrating the immense human cost of the project.

Standing between 180 and 200 centimeters tall and weighing approximately 200 kilograms, the soldiers of the Terracotta Army are strikingly lifelike. Each figure displays a distinct personality, conveyed through subtle variations in facial features, expressions, and hairstyles. Together, they represent a wide range of military formations and ranks, reflecting the highly organized structure of the Qin army. Among them are infantrymen, chariot warriors, and cavalrymen, with infantry forming by far the largest group. These infantrymen may have served either as members of large, coordinated units or as independent formations. Distinctions between individual soldiers and military units are clearly expressed through variations in armor, posture, and hairstyle. The armored infantry figures can be divided into three distinct groups based on their hairstyles. Solders in the first group wear their hair tied into a topknot positioned on the right side of the head. In the second group, the hair is tightly bound at the back of the head but not formed into a topknot. In the third group, the gathered hair is concealed beneath a small textile cap, drawn tight at the back to prevent it from shifting during movement. These subtle yet deliberate variations enhance the realism of the figures and underscore the Qin dynasty’s emphasis on military order and visual differentiation. Altogether, an estimated 8,000 terracotta figures have been discovered across the excavation pits. When unearthed, all were found shattered into numerous fragments, many bearing traces of burning. Upon examination, this evidence suggests deliberate human intervention, although the exact cause and circumstances of the destruction remain uncertain. Restoring a single figure is an exceptionally complex and time-consuming process: conservators must carefully clean, catalog, and analyze hundreds of fragments before reassembling them into a coherent whole – a painstaking task that can take up to three years to complete.

The largest and most impressive of the three pits, Pit No. 1, has a rectangular ground plan oriented along an east–west axis and measures approximately 230 meters in length and 62 meters in width. It was sunk nearly 5 meters into the ground and reinforced to ensure long-term stability. The pit is divided into eleven long, parallel corridors by massive rammed-earth partition walls measuring about 3.2 meters in height and 2 meters in width. These walls supported a roofing system of heavy wooden rafters laid crosswise, which were covered with layers of straw and compacted earth to form a stable ceiling. The pit floor was firmly rammed and paved with bricks, providing a solid foundation. Within this vast archaeological space, thousands of armored and unarmored infantry soldiers stand arranged in disciplined battle formation. The nine central corridors constitute the main body of the army, with four soldiers standing abreast in each column, creating a dense and orderly core formation. Along the outer edges, pairs of soldiers are positioned as flank-guards, designed to protect the formation from lateral attack. At both the front and rear of the pit, the vanguard and rearguard are formed by soldiers standing abreast, creating a defensive screen three rows deep. Each corridor contains approximately 560 soldiers, while more than 200 warriors are stationed along each flank. Enhancing the striking power of the infantry, six war chariots – each drawn by four horses – are strategically positioned within six of the central corridors, reflecting the integrated use of chariots and infantry in Qin military tactics. In addition, approximately 40,000 bronze weapons, primarily arrowheads, have been recovered from Pit No. 1. Many of the swords remain remarkably sharp, protected by a layer of chromium oxidation that points to highly sophisticated manufacturing techniques. These were not merely symbolic objects but functional weapons, likely used in warfare before being interred with the Terracotta Army.

Pit No. 2 differs markedly from Pit No. 1 in both layout and function. Shaped in an L-form and only partially excavated, this pit contains a smaller but more versatile mixed combat force composed of a large squadron of war chariots, armored cavalrymen standing in front of their horses, and a contingent of archers and infantrymen. Unlike the massive infantry formation of Pit No. 1, the troops in this pit represent a flexible strike unit capable of rapid movement and responsive to changing battlefield conditions. The eastern section of the pit is dominated by an archer formation that highlights the sophistication of Qin ranged warfare. Along the outer edge stand 172 standing archers, positioned to deliver continuous volleys toward the enemy. Behind them, in four interior corridors, are 160 kneeling, armored archers arranged in tightly ordered rows. This deliberate spatial organization reflects the practical demands of archery in battle: while one group fired, the other reloaded, ensuring an uninterrupted flow of arrows. The timing of shooting and reloading corresponded precisely with the rotation of positions between the standing archers at the perimeter and the kneeling archers behind them. This alternating system maximized firepower while maintaining defensive stability, demonstrating a high level of tactical planning and discipline within the Qin army. The archers were equipped with crossbows featuring sophisticated bronze trigger mechanisms that allowed the bow to remain drawn without continuous physical effort and were powerful enough to fire arrows over distances exceeding 800 meters.

The U-shaped Pit No. 3 is the smallest of the three archaeological pits and the only one to have been fully excavated; yet it is arguably the most significant in terms of military hierarchy, as it represents the command headquarters of the Qin army. The pit contains 68 high-ranking officers, four horses, a wooden war chariot, and 34 weapons. Architecturally, the pit is divided into three distinct sections, each corresponding to a specific function within the command unit. At its center stands a war chariot drawn by four horses, once richly lacquered and carefully positioned as the focal point of the space. Behind this centrally placed chariot stand four charioteers, whose role extended beyond merely driving the vehicle. They were responsible for transmitting military commands and assisting the commanding general in directing the course of battle. Drums and bells – essential instruments of ancient warfare – were used to signal maneuvers and to inspire courage among the soldiers on the battlefield. Surrounding this central command area are figures of officers arranged in orderly formation, underscoring the strict hierarchy and chain of command that characterized the Qin military system.

Scholars continue to debate how the thousands of soldiers of the Terracotta Army were made, reflecting the extraordinary scale and sophistication of the project. According to many Chinese researchers, each figure was crafted as a unique individual. Evidence supporting this view includes visible traces of potters’ tools on the interior surfaces of the figures, fingerprints and handprints left by craftsmen during shaping, and inscriptions bearing the names of individual artisans or workshops carved or stamped onto the statues. A different and influential interpretation was advanced by the German sinologist Lothar Ledderose, who described the creation of the Terracotta Army as an early form of mass production. In his view, the figures were manufactured using a modular system: standardized components such as arms, legs, and torsos were produced in molds, and then assembled in a variety of combinations. After assembly, surface details were refined by hand, allowing for variation within an otherwise standardized framework. This method would have enabled the Qin state to produce thousands of figures efficiently while maintaining a high degree of visual diversity. Despite their differences, both interpretations agree that the heads were made separately from the bodies, individually modeled, and fired independently before being attached. After firing, the statues were painted in vivid colors – including reds, blues, greens, and purples – to enhance their realism. Although much of this pigmentation had faded or flaked away since excavation, traces of the original paint survive and can be scientifically analyzed, allowing scholars to reconstruct the army’s original, brightly colored appearance. This highly organized system of production in which responsibility and quality control were carefully monitored, while still allowing room for individual craftsmanship, resulted in a vivid portrayal of a Qin army rather than a mass of identical statues.

Taken as a whole, the mausoleum complex represents one of the most ambitious and complex burial projects ever undertaken, mirroring the structure and functions of Qin Shi Huang’s earthly rule. Conceived as a complete and faithful replica of the empire, it was intended to ensure that the First Emperor would continue to exercise authority, command armies, and uphold cosmic order in the afterlife just as he had during his lifetime.

Today, the archaeological complex – encompassing the central burial mound, the renowned Terracotta Army, and hundreds of ancillary tombs, trenches, workshops, and architectural remains – forms the Emperor Qinshihuang’s Mausoleum Site Museum, a UNESCO World Heritage Site dedicated to the preservation, excavation, and interpretation of the First Emperor’s funerary landscape. Through a combination of in situ displays, purpose-built exhibition halls, and ongoing archaeological research, the museum offers visitors a comprehensive understanding of the scale, organization, and symbolic meaning of Qin Shi Huang’s mausoleum, while also highlighting the technical achievements and historical significance of the Qin dynasty. As excavations and research are still ongoing, the site remains a living archaeological landscape, constantly yielding new discoveries.

Sources

https://www.bmy.com.cn/jingtai/bmyweb/index.html

https://www.sxhm.com/en/index.html?_isa=1

https://www.bjqtm.com/

https://en.chnmuseum.cn/