Mihály Munkácsy, one of the most celebrated painters of the 19th century, created powerful visual narratives filled with emotional depth through his masterful compositions – often centered around a single, compelling figure – and his refined painterly technique.

Mihály Munkácsy was born in Munkács, Hungary (now Munkachevo, Ukraine) on February 20, 1844. After losing both of his parents, he went to live with his uncle, the lawyer István Reök, in 1851, at the age of seven. Munkácsy, disliking the confines of formal schooling, was apprenticed by his uncle to a craftsman in Békéscsaba, where he eventually became a carpenter. However, he soon realized that his aspirations lay elsewhere. In 1861, he became an apprentice to the itinerant painter Elek Szamossy in Gyula. He later gained the patronage of the landscape painter Antal Ligeti in Budapest and went on to study at the Vienna Academy of Art under Karl Rahl, followed by further training at the Munich Academy of Art. At just 23 years old, Munkácsy had his first painting, Vihar a pusztán [Storm on the Puszta], purchased by the Magyar Nemzeti Múzeum [Hungarian National Museum]. His choice of subject matter was influenced by the Hungarian painter Károly Lotz (1833–1904), whose depictions of the Alföld landscape were highly popular at the time. That same year, he traveled to Paris on a scholarship to attend the 1867 World Exposition, where the works of two leading French Realist painters, Gustave Courbet (1819–1877) and Jean-François Millet (1814–1875), left a profound impression on the young, aspiring artist.

“I don’t want to offend you,” [Than Mór] began tactfully, “but first, let me say that this painting, which you call a ‘light sketch’, is striking – it stops a person in their tracks and, in the best sense of the word, is astonishing. If it had even the slightest precedent, or if there were the faintest trace of conscious intent behind it, I would have to call it a masterpiece. But since it has neither a prelude nor a continuation, and since you yourself admit that you don’t know what to do with it, I can only see it as a fleeting moment of the soul’s intoxication in the face of a vision. Still, I believe this soul resides in a remarkably talented and exceptionally strong individual – someone I must urge to study, to study immensely and relentlessly, and to work without cease. If you do, I believe that in eight to ten years, you may well become one of the greatest masters in Europe.”

Sándor Dallos: A nap szerelmese (1958)

After years of dedicated study, relentless hard work, and struggles with illness and financial hardship, 1868 marked a turning point in Munkácsy’s life – igniting one of the most remarkable legends in 19th-century Hungarian art history. He continued his studies at the Düsseldorf Academy of Art under the renowned genre painter Ludwig Knaus. It was there, shaped by his experiences and impressions, that Munkácsy began to find his own artistic voice. During this period, he painted Siralomház [The Condemned Cell], a striking realistic portrayal of a Hungarian bandit’s final farewell awaiting execution. The theme resonated deeply with Hungarian audiences, as banditry was often romanticized at the time. Following the defeat of the 1848-49 War of Independence, many men became homeless wanderers, seeking to avoid conscription into the Austrian Imperial Army. Living as outlaws in the wilderness, they survived by robbing wealthy travelers. Once captured, they were sentenced to death. According to Munkácsy’s correspondence, “one fine Friday”, an “Englishman” – most likely the American industrialist William P. Wilstach (1816–1870) – visited his studio, examined the unfinished painting, and purchased it on the spot for the extraordinary sum of 10,000 francs. At the buyer’s request, the painting was first exhibited at the 1870 Paris Salon, the most prestigious international art exhibition of its time. There, Siralomház was awarded a gold medal, marking the first international success of the young and previously unknown Hungarian artist. This distinction changed Munkácsy’s life overnight, launching him as a celebrated name in European art. The dramatic power of the painting impressed leading Realist painters of the time, including the Frenchman Gustave Courbet (1819–1877) and the German Wilhelm Leibl (1844-1900), the latter expressing his admiration in a heartfelt letter that Munkácsy treasured in his wallet for the rest of his life. During this period, he also became acquainted with Baron Édouard de Marches of Luxembourg and his wife, who became his devoted patrons.

Encouraged by his friends and buoyed by the success of Siralomház, Munkácsy relocated to Paris in the winter of 1871–72. At the time, the city was a bustling, cosmopolitan capital and a vibrant hub for artists from all over the world. Yet, despite his rising fame, Munkácsy soon found himself gripped by a profound creative crisis. The pressure to follow up on his first major international triumph, coupled with internal struggles and uncertainty about his artistic direction, left him in a state of turmoil. Seeking solace and clarity, he accepted an invitation from his lifelong friend and fellow painter, László Pál, to join him at the Barbizon art colony, nestled in the Forest of Fontainebleau. There, among kindred spirits and beneath the towering trees, Munkácsy found refuge. The artists of the Barbizon School were reshaping the genre of landscape painting by working en plein air, capturing fleeting light, atmosphere, and emotion through loose brushwork and softened forms. One of the best examples of this influence on Munkácsy is Rőzsehordó nő [Woman Carrying Brushwood], now regarded as one of the most iconic Hungarian paintings. Reproductions of it were once widely displayed in both private homes and public places. The months spent in Barbizon, marked by both introspection and creative renewal, helped Munkácsy overcome his artistic impasse – ultimately leading to the creation of his next major painting, Éjjeli csavargók [Tramps at Night]. This deeply moving depiction of vagrancy resonated with the social conscience of post-war France, where the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War had left many destitute. The painting earned Munkácsy his second gold medal at the 1874 Paris Salon. That same year marked a turning point in his personal life as well: he married the widowed Baroness Cécile Papier, whose noble status and considerable wealth significantly elevated his social standing.

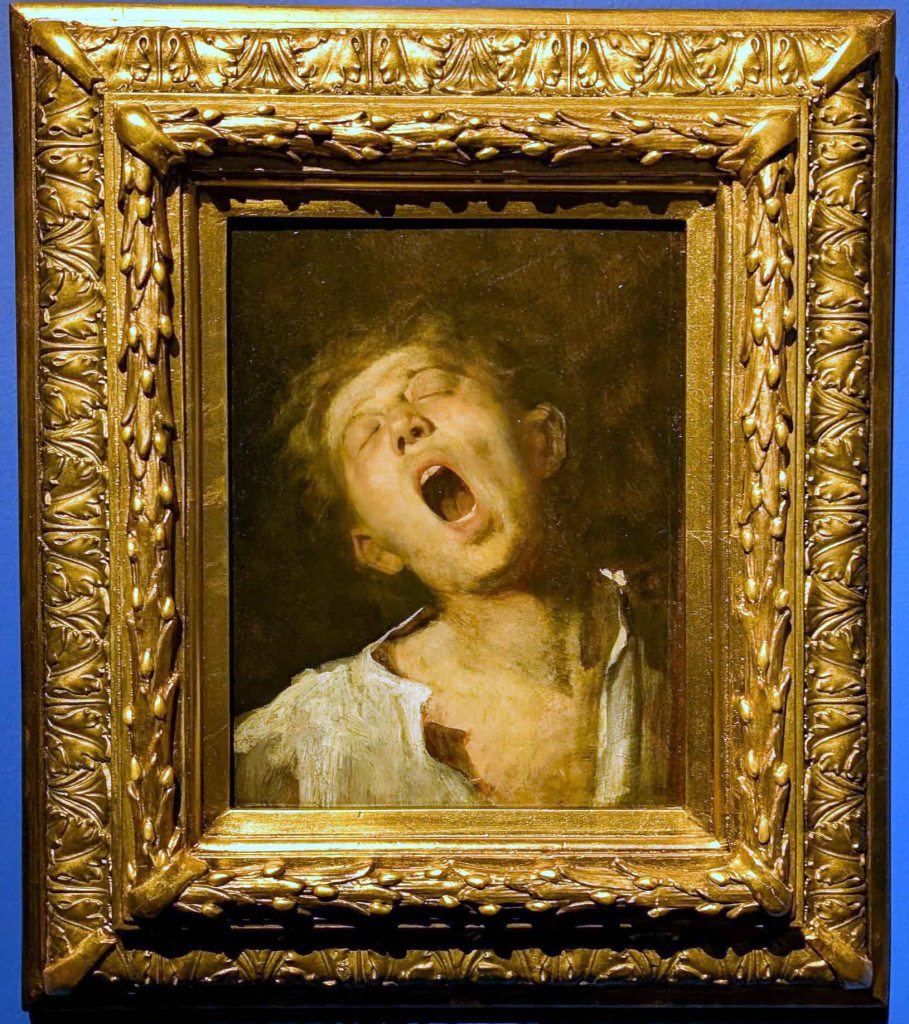

Munkácsy continued to exhibit regularly at the prestigious Paris Salon, steadily gaining acclaim from both critics and the public. He deliberately aligned himself with the highly popular international trend of Realists genre painting – a movement that not only reflected the social realities of the 19th century but also laid critical groundwork for the emergence of modern art. A key factor in Munkácsy’s sustained success was his careful choice of subject matter. By focusing on scenes from everyday life and individuals living on the fringes of society – those worn down by hardships and marked by social exclusion – he struck a chord with a broad and empathetic audience. His depiction of marginalized figures, rendered with psychological depth and atmospheric nuance, captivated Parisian viewers, who found the unfamiliar customs and rural themes both intriguing and exotic. Notable works from his Realist period include Ásító inas [Yawning Apprentice] (1869), Siralomház [Condemned Cell] (1870), Köpülő asszony [Woman Churning Butter] (1873), Rőzsehordó nő [Woman Carrying Brushwood] (1873), Éjjeli csavargók [Tramps at Night] (1873), Zálogház [Pawnbroker’s Shop] (1874), and Újoncok [Recruitment] (1877). Each of these paintings showcases his mastery in composition, his keen observation of human emotion, and his commitment to the Realist ethos.

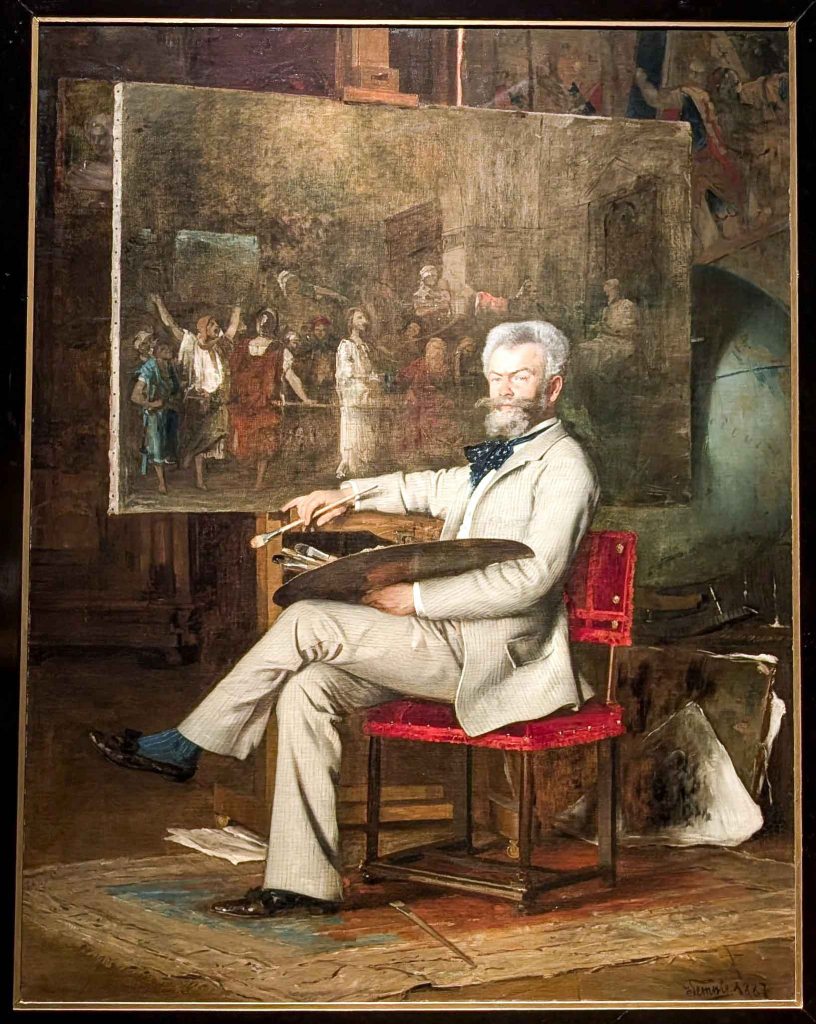

The painting Műteremben [In the Studio] (1876) marks a new artistic credo within Munkácsy’s body of work. While its style still reflects the influence of earlier Realist genre scenes, its subject matter foreshadows the more intimate and refined Salon paintings. This double portrait features a full-length self-portrait of Munkácsy, elegantly dressed and presented as a successful and influential bourgeois figure, alongside his wife, Cécile Papier, portrayed as a truly modern woman. The painting conveys a vision of a new artistic era and the rise of a bourgeois class of artists. His first major work in this emerging style, Párizsi Enteriőr [Parisian Interior] (1877), clearly illustrates this shift. Additionally, Munkácsy’s profound interest in the fundamental questions of human existence led him to create Milton (1878), a philosophical masterpiece that earned an honorary gold medal at the 1878 World Exposition in Paris. That same year, he signed a ten-year exclusive contract with Charles Sedelmeyer (1837–1925), a prominent Parisian art dealer who steered Munkácsy’s career in a new direction – toward unprecedented wealth and international acclaim. At Sedelmeyer’s suggestion, Munkácsy also created replicas (second versions painted by his own hand) and reductions (scaled-down versions, typically half the original size) of his most popular works.

The dealer also encouraged him to continue creating Salon paintings, which were highly fashionable at the time, in order to further establish the painter’s brand. Munkácsy depicted social gatherings among the upper class, set in luxurious interiors – often drawing inspiration from his own elegant mansion in one of Paris’ most distinguished quarters. To satisfy his deep desire for artistic freedom, he occasionally stepped away from the confined spaces of opulent salons, applying the refined style of Salon painting to outdoor scenes as well. These works featured rich colors and dynamic textures, portraying more intimate, event-free moments in the lives of the French elite. By this time, his lavishly furnished mansion had become a prestigious venue for soirées and a showcase for his latest works. A carefully selected circle of admirers and collectors eagerly acquired these paintings, viewing them as unique mementos of the artist. Most of these works eventually made their way overseas, acquired by prominent private collections in the United States. His most notable paintings from this period include Pávák – Reggeli a kertben [Peacocks – Breakfast in the Garden] (1878), Két család a szalonban [Two Families in the Salon] (1880), Reggel a nyaralóban [Morning in the Country House] (1881), Sétány a Monceau Parkban [Walkway in Parc Monceau] (1882), and Pamlagon ülő fiatal nő [Young Woman Sitting on a Sofa] (1887).

As further recognition of his achievements, Munkácsy was granted a noble title by the Habsburg monarch, Emperor Franz Joseph (reign: 1848–1916), in 1880. To continue building his brand, his art dealer Sedelmeyer encouraged him to explore the theme of the Passion of Christ – a subject widely favored by painters for its profound emotional and spiritual resonance. At the time, monumental paintings of all genres were immensely popular across Europe, captivating audiences not only with their grand scale but also with their universal themes and dramatic narratives. The Passion offered both. According to the biblical account, after being accused by the Jewish high priests led by Caiaphas, Jesus was sentenced to death. However, they needed the Roman governor, Pontius Pilate, to authorize the execution. In his first monumental work, Krisztus Pilátus előtt [Christ before Pilate] (1881), Munkácsy depicted the crucial moment of Christ’s first appearance before Pilate – when the Roman governor grapples with the decision of whether to yield to the priests’ demands and condemn a man he considers innocent under Roman law. The painting’s powerful composition, emotional intensity, vividly rendered characters deeply moved viewers and established Munkácsy’s reputation as a master of large-scale historical painting.

While Krisztus Pilátus előtt was still on display, Munkácsy began working on its thematic continuation, Golgotha (1884). This painting captures the climatic moment of the Passion, depicting Jesus on the Cross, with St. John the Evangelist and the three Marys gathered at his feet. Dark storm clouds loom in the background, intensifying the composition’s dramatic effect. Munkácsy’s portrayal of Christ resonated deeply with audiences across cultures and borders. Beyond its monumental scale and compelling subject matter, the painting’s emotional impact lay in its lifelike realism – a testament to the artist’s technical mastery. The Christ paintings were exhibited throughout Europe and the United States, attracting more than 2 million visitors. In 1887, following the tour, both paintings were purchased by American millionaire businessman John Wanamaker for a record-breaking sum – making Munkácsy the most expensive living painter of his time. With the moment ripe and determined to nurture future talent while solidifying his legacy, he established a scholarship to support young Hungarian painters

At the height of his career, Munkácsy received two prestigious official commissions that marked a defining moment in his artistic journey. In 1890, he completed Reneszánsz apoteózis [Renaissance Apotheosis], a ceiling fresco for the main staircase of the Kunsthistorisches Museum [Art History Museum] in Vienna. This grand tribute to the Italian Renaissance depicts a temple-like artist’s studio, where the architect Bramante presents the plans for the new Basilica di San Pietro [St. Peter’s Basilica] to Pope Giulio II (papacy: 1503-1513). The scene features renowned Renaissance painters – Titian with Veronese, Leonardo with Raphael, and Michelangelo – and includes a self-portrait of Munkácsy, standing behind the nude female models.

The same year, the Hungarian state commissioned Honfoglalás [Hungarian Conquest], intended for the Országház [Hungarian Parliament Building], which was then under construction in Budapest. This work is the second-largest historical painting in Hungary, surpassed only by Árpád Feszty’s panoramic masterpiece A magyarok bejövetele [Arrival of the Hungarians] (1895). Munkácsy’s composition illustrates the legend of the white horse: after the ambassadors of Grand Prince Árpád presented a white horse as a gift to the Slavic ruler Svatopluk, the ruler’s envoys offered soil, grass, and water in return – symbolically ceding authority over the territory of Pannonia to the Hungarians. The subject was especially relevant as Hungary approached its millennium – the thousandth anniversary of the state’s foundation in the Carpathian Basin. Munkácsy strived for historical authenticity, meticulously researching period attire and other details. The painting was unveiled on February 24, 1894, at the Magyar Nemzeti Múzeum [Hungarian National Museum].

French critic’s review of the Hungarian Conquest, exhibited at the 1893 Salon:

“Munkácsy’s Árpád, both in scale and artistic value, is the most remarkable work in the Salon. First and foremost, it must be noted that its impact is owed entirely to the artist himself, not to the subject matter – since, for us French, the subject holds little interest and certainly lacks inspiration. This achievement is purely the result of the painter’s talent. And that talent is considerable: he was tasked with depicting an event that is almost entirely unknown to us and, therefore, lacks inherent appeal. We have scarcely heard of the principal figures portrayed, and the period in question belongs to the dawn of the Middle Ages. How, then, did he succeed not only in capturing our attention but in halting us, captivating us, and compelling us to strive to understand the painting? In short, what is it about this painting that so deeply interests us? It is the fact that the artist made it entirely his own – he loved it deeply and was so passionately devoted to it that he compels us, in turn, to know the painting, to reflect on it, to judge it, and ultimetly to love and admire it.”

Dezső Malonyai: Munkácsy Mihály (1907)

The final piece of the Christ trilogy, Ecce Homo, was unveiled at the 1896 National Millennium Exhibition in Budapest. For Munkácsy, having a strong presence at the celebrations held deep personal significance. The painting depicts Christ’s final encounter with Pilate, during which the crowd is given a choice to spare one prisoner from execution. At their insistence, the Roman governor releases the criminal Barabbas. In the scene, Pilates presents the scourged Christ – crowned with thorns – and utters the now-famous words: Ecce Homo! [Behold the man!] Many believe that Munkácsy portrayed Christ as a self-portrait, reflecting his own suffering, as he battled a terminal illness and witnessed waning interest in his work amid the rise of new artistic movements. Despite his declining health, he undertook this final monumental painting with the support of his students. Though he attended the celebrations, he fell ill during one of the evening receptions, marking his final public appearance. Munkácsy passed away on May 1, 1900, in a quiet sanatorium in Endenich, Germany – far from the brilliance of the salons that had once celebrated his genius.

“Perhaps what strikes one most in the picture under consideration [Ecce Homo] is the sense of life, the realistic illusion. One could well fancy that the men and women were of flesh and blood, stuck into silent trance, by the warlock’s hand. Hence the picture is primarily dramatic, not an execution of faultless forms, or a canvas reproduction of psychology. By drama I understand the interplay of passions; drama is strife, evolution, movement, in whatever way unfolded. …the whole [thus] forms a wonderful picture, intensely, silently dramatic, waiting but the touch of the wizard wand to break out into reality, life and conflict. As such too much tribute cannot be paid to it, for it is a frightfully real presentment of all the baser passions of humanity, in both sexes, in every gradation, raised and lashed into a demoniac carnival. …It is grand, noble tragic but it makes the founder of Christianity, no more than a great social and religious reformer, a personality, of mingled majesty and power, a protagonist of a world-drama.”

James Joyce: Royal Hibernian Academy ‘Ece Homo’ (1899)

Today, Mihály Munkácsy’s paintings are housed in prestigious museums and private collections around the world, testifying to his enduring legacy and international acclaim. The most comprehensive collection of his works can be found at the Magyar Nemzeti Galéria [Hungarian National Gallery] in Budapest. This extensive collection, which includes most of the paintings discussed in this essay – from his early Realist works to his later Salon-style pieces – offers insight into the evolution of his artistic career. After many years of wandering, the monumental Christ Trilogy has found a permanent home in the Déri Múzeum in Debrecen, where it continues to attract thousands of visitors. Tragically, Munkácsy never lived to see the three paintings displayed together, as he passed away before their final reunion. The massive historical painting, Honfoglalás [Hungarian Conquest], is prominently displayed in the Országház [Hungarian Parliament Building] in Budapest, a symbolic location befitting the painting’s national significance. Munkácsy’s early life and personal history are preserved in Békéscsaba, where two museums are dedicated to his memory. The Munkácsy emlékház [Munkácsy Memorial House], located in the residence where he spent part of his childhood, offers intimate insight into his formative years. Meanwhile, the Munkácsy Múzeum [Munkácsy Museum] houses a small collection of his paintings as well as unique artifacts, documents, and memorabilia related to his life and career. Beyond Hungary’s borders, several of Munkácsy’s most important works are held in major institutions. His painting Milton, which earned him great acclaim, resides in the New York Public Library, while Reneszánsz apoteózis [Renaissance Apotheosis], his celebrated ceiling fresco, continues to adorn the main staircase of the Kunsthistorisches Museum [Art History Museum] in Vienna.

Sources

Munkácsy, Mihály (2016) Emlékeim

Malonyai, Dezső (1907) Munkácsy Mihály

https://mng.hu/

https://www.szepmuveszeti.hu/