Like Jordan itself, Amman is a modern capital where layers of history and modernity seamlessly intertwine across its hills and valleys.

Spread across a series of steep hills known as jebels, Amman has witnessed continuous human settlement since the Neolithic period, making it one of the oldest continuously inhabited places in the region. Archaeological evidence suggests that early communities settled here as early as the 8th millennium BC, drawn by the area’s natural springs and strategically advantageous highlands. By the 13th century BC, the area was known as Rabbath Ammon, the capital of the Ammonite Kingdom. Situated along the King’s Highway – an ancient trade route connecting Egypt with Mesopotamia – the city prospered from commercial traffic and the wealth it generated. The Ammonites built massive defensive walls and developed a thriving city-state that played a significant role in the geopolitics of Iron Age Transjordan. Over time, the city came under the control of powerful empires. It was conquered by the Neo-Assyrians in the 8th century BC, followed by the Neo-Babylonians in the 6th century BC, and later the Achaemenid Persians – each leaving a distinct mark on its urban landscape and political structure.

The Near East was later conquered by Alexander the Great of Macedon (reign: 336-323 BC), though little is known about Macedonian rule over Transjordan. After Alexander’s death, during the Hellenistic period, the region came under the control of the Ptolemies, and the city was renamed Philadelphia in honor of Pharaoh Ptolemy II Philadelphus (reign: 284–246 BC), who ruled from Egypt. Under this new name and Hellenistic influence, Philadelphia flourished – marked by Greek-style architecture, administrative reforms, and vibrant cultural exchange. In 63 BC, the Romans annexed much of the Levant, and Philadelphia became one of the ten cities of the Decapolis League – a federation of self-governing, Hellenized towns on the eastern frontiers of the Roman Empire, linked by shared economic and cultural interests. This period witnessed a surge in urban development and monumental construction, traces of which still grace modern Amman: the grand Roman Theatre, which could seat up to 6,000 spectators; the smaller Odeon for music and poetry performances; the Nymphaeum, a public fountain complex dedicated to water nymphs; and the Citadel atop Jebel al-Qal’a, a strategic high point in use since the Bronze Age.

During the early Islamic period, the city once again rose to prominence. Recognizing the Citadel’s enduring strategic and symbolic value, the Umayyads constructed a palace complex there in the 8th century. It included an audience hall, mosque, residential quarters, and water cisterns – an impressive example of early Islamic architecture that blended local building traditions with Umayyad design. Following the decline of the Umayyad Caliphate and subsequent regional upheavals, Amman gradually faded into obscurity. The once-thriving city, stripped of its political and economic significance, languished in silence for centuries. Its former grandeur was buried beneath layers of time; its name slowly fading from maps and memory. Monumental ruins crumbled and were reclaimed by nature, visited only occasionally by wandering travelers and nomadic Bedouin herders.

Amman’s modern resurgence began in the early 20th century, amid the geopolitical reshaping of the Middle East following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. In 1921, the Hashemite Emir – and later King – Abdullah I (reign: 1946-1951) designated Amman as the capital of the newly formed Emirate of Transjordan, which became the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan in 1950. He recognized the city’s central location and its symbolic resonance as a site of profound historical significance. At the time, Amman was still a modest village with a population of only a few thousand and limited infrastructure. But it quickly emerged as the political, economic, and cultural center of the nascent Jordanian state. Throughout the 20th century, the city expanded rapidly – driven by waves of migration, urbanization, and regional conflict. Palestinian refugees arrived in large numbers after the 1948 Arab-Israeli War and the 1967 Six Day War, followed in later decades by Iraqis, Syrians, and other communities fleeing regional unrest. This demographic transformation infused Amman with diverse cultural influences, while also placing considerable strain on its infrastructure and housing. Despite these challenges, the city evolved into a dynamic capital – marked by rapid modernization, sprawling neighborhoods, and a steadily growing economy.

Today, Amman is a vibrant and multifaceted metropolis – an essential stop on any ultimate Jordanian road trip. It is a city of contrast, where sleek glass towers and modern shopping malls rise above ancient ruins, and where centuries-old traditions coexist with cosmopolitan modernity. Amman serves not only as the political and economic heart of Jordan but also as a cultural crossroads for the wider region. It stands as a living bridge between the country’s storied past and its aspirations for the future, embodying the resilience and adaptability that have shaped the nation’s journey through history.

Downtown

Undoubtedly, the most captivating district of Amman is Downtown – a vibrant, chaotic, and atmospheric quarter that serves as the city’s commercial, religious, and cultural heart. Its bustling souks [markets] wind through narrow alleyways and shaded arcades, brimming with color, sound and, scent. Vendors enthusiastically sell everything from marinated olives, pickled vegetables, spices, and herbs to live poultry, secondhand books, antiques, handwoven rugs, and gold jewelry. The air is thick with the aroma of cardamom-infused coffee, sizzling falafel, and freshly baked pastries – occasionally mingled with the pungent smell of animal excrement. Overhead, tangled electric wires crisscross the skyline, and the soundscape becomes a symphony of haggling voices, honking cars, prayer calls, and the rhythmic tapping of cobblers and craftsmen at work.

Dominating the area is the Grand Hussein Mosque, a focal point of religious life in Amman. Built in 1924 on the foundations of a 7th-century Umayyad mosque, it remains one of the city’s most important and well-attended places of worship. On Fridays, the mosque becomes the beating heart of the district, with surrounding streets filled with worshippers, merchants, and street vendors in a dynamic display of faith and commerce.

Just a short walk away stands the Roman Nymphaeum, constructed in the 2nd century AD as a grand public fountain and pool complex dedicated to the water nymphs of Roman mythology. Though now partially ruined, its still-imposing arches and surviving niches offer a glimpse into the sophistication of Roman urban planning and the cultural importance of water in ancient city life. The site provides a surprisingly tranquil counterpoint to the clamor of the modern city just beyond its walls.

However, Amman’s most iconic Roman monument is undoubtedly the Roman Theatre, also dating back to the 2nd century AD. Carved into the northern slope of a hill to shield spectators from the harsh desert sun, the theatre originally seated up to 6,000 people. Remarkably well-preserved, it is still used today for concerts and cultural festivals, echoing its ancient role as a center of public life. Notably, the theatre’s uppermost tiers were carved into a pre-existing necropolis – a distinctly Roman gesture that blended layers of the city’s past. At the base of the theatre lies a Corinthian colonnade, as well as the Odeon, a smaller venue designed for more intimate musical and poetic performances.

Beneath the theatre are two modest yet engaging museums. The Folklore Museum offers insight into Jordan’s rural and Bedouin heritage, with exhibits featuring embroidered garments, a traditional goat-hair Bedouin tent, coffee-making tools, and musical instruments such as the rababa – a one-stringed bowed instrument still played at weddings and storytelling gatherings. Adjacent to it, the Museum of Popular Traditions highlights Jordan’s ethnic and religious diversity, through displays of Circassian and Armenian silver jewelry, intricately beaded bridal dowries, and protective amulets fashioned from Turkish coins. Among its most striking exhibits are ‘Hand of Fatima’(Hamsa) amulets and intricately embroidered dresses from across the Levant. The museum also houses a collection of exquisite mosaics recovered from ancient churches in Jerash and the baptism site at Wadi al-Kharrar, offering a compelling visual connection to Jordan’s rich religious and cultural heritage.

Citadel (Jebel el-Qal’a)

More than anything, Amman is a city of jebels [hills], and none is more historically and symbolically significant than Jebel el-Qal’a. Perched high above the city center, this elevated promontory has served as the fortified heart of Amman for millennia. Its strategic location attracting a succession of civilizations whose layered legacies still shape the site. With panoramic views that stretch across both ancient ruins and modern neighborhoods, the Citadel encapsulates the very essence of Amman’s historical continuity.

The earliest known structure on the site is a Bronze Age cave with rock-cut tombs, dating back to the 19th century BC, suggesting that the area was used for ritual or burial purposes by early communities. By the 13th century BC, Jebel el-Qal’a had become the capital of the Ammonite Kingdom, serving as its royal and religious center. The ruins of the Ammonite Palace, with its thick stone walls and ceremonial platforms, testify to the kingdom’s political authority. Archaeological excavations have unearthed significant artifacts from this period, including terracotta figurines, limestone statues, Phoenician ivory inlays, and imported luxury goods – evidence of Amman’s integration into Iron Age trade networks extending across Egypt, Mesopotamia, and the Levantine coast.

The most striking remnant of the Roman period is the Temple of Hercules, constructed during the reign of Emperor Marcus Aurelius (reign: 161–180 AD). Its monumental Corinthian columns, some rising over 10 meters high, dominate the skyline and remain a powerful testament to Roman architectural ambition. The temple likely stands atop an earlier sanctuary dedicated to Milkom, a major deity of the Ammonites. Under Roman rule, it was rededicated to Hercules, who was revered in the eastern provinces as a syncretic hero-god. Annual festivals held in his honor at the temple attracted pilgrims and merchants, contributing to the city’s cultural and economic vitality.

Along the southern slope of the Citadel, archaeologists have uncovered a multi-period residential quarter that remained in use during the Roman, Byzantine, and Umayyad periods. A partially preserved Byzantine house still bears traces of mosaic flooring, while a nearby Byzantine church attests to the site’s continued religious importance into the Christian era. These layers reflect a remarkable continuity of urban habitation and evolving sacred spaces.

The Umayyad Palace complex, constructed around 750 AD, is the best-preserved structure on the Citadel. Although it was abandoned shortly after the fall of the Umayyad Caliphate, the palace remains a compelling example of early Islamic architecture that blended Greco-Roman, Persian, and local design traditions. The complex includes a domed audience hall, a mosque, cisterns, and administrative quarters, all arranged around a central courtyard – a layout that reflects both practical planning and ceremonial grandeur.

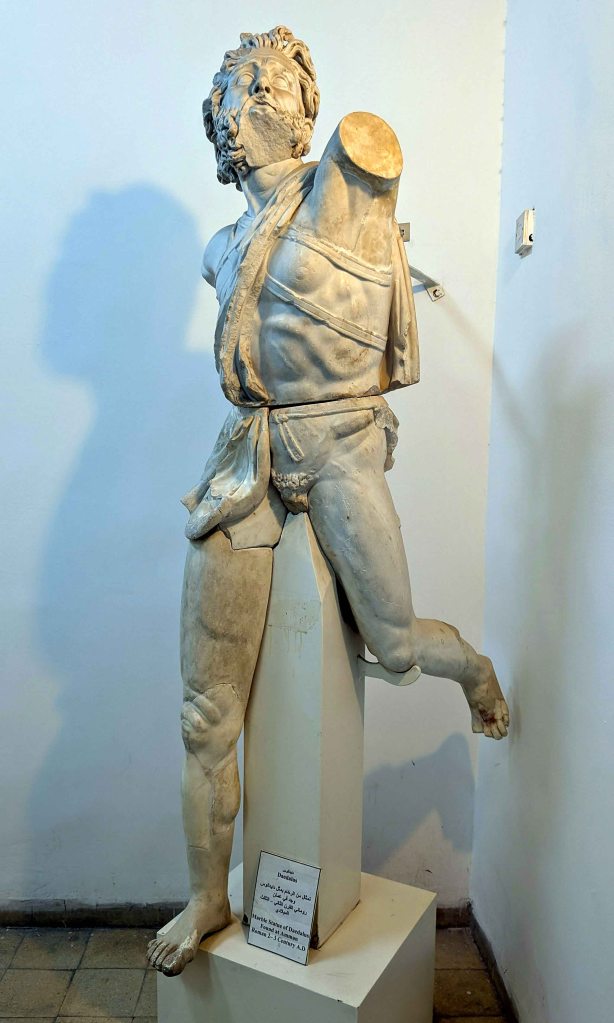

At the heart of the Citadel stands the Jordan Archaeological Museum, a compact yet invaluable collection of artifacts spanning over 8,000 years of Jordan’s history. Among its most prized pieces is a Neolithic two-headed statue from Ain Ghazal – one of the earliest known large-scale representations of the human form – alongside Ammonite stone busts, Nabataean sculptures and ceramics from Petra, a Roman sculpture of Daedalus, and intricately carved Umayyad-era objects. Though modest in size, the museum offers a profound glimpse into the civilizations that shaped not only Amman but the wider region.

Despite decades of archaeological work, much of the Citadel remains unexcavated, its layers of rubble still concealing stories yet to be told – silent witnesses to Jordan’s deep and complex past.

Jordan Museum

The Jordan Museum in Amman stands as the country’s premier cultural institution, offering a compelling window into the deep and diverse history of Jordan. More than a mere repository of artifacts, the museum serves as a dynamic space where visitors can trace the evolution of civilization in the region – from prehistoric settlements to modern nationhood. Through carefully curated exhibits, it highlights Jordan’s central role in the ancient world and the enduring continuity of its cultural legacy.

Among the museum’s most captivating exhibits are the Ain Ghazal statues, including the famous two-headed figures, which date back to the 8th millennium BC. Sculpted from lime plaster and reed, these Neolithic statues are among the oldest known large-scale depictions of the human form. Their hauntingly expressive features suggest a spiritual or ritualistic purpose, though their exact function remains a mystery. Intriguingly, many of the figures were deliberately buried shortly after their creation, leading archaeologists to speculate that they may have been crafted specifically for ritual deposition. These statues offer a rare and intimate glimpse into prehistoric belief systems and early artistic expression at the dawn of human civilization.

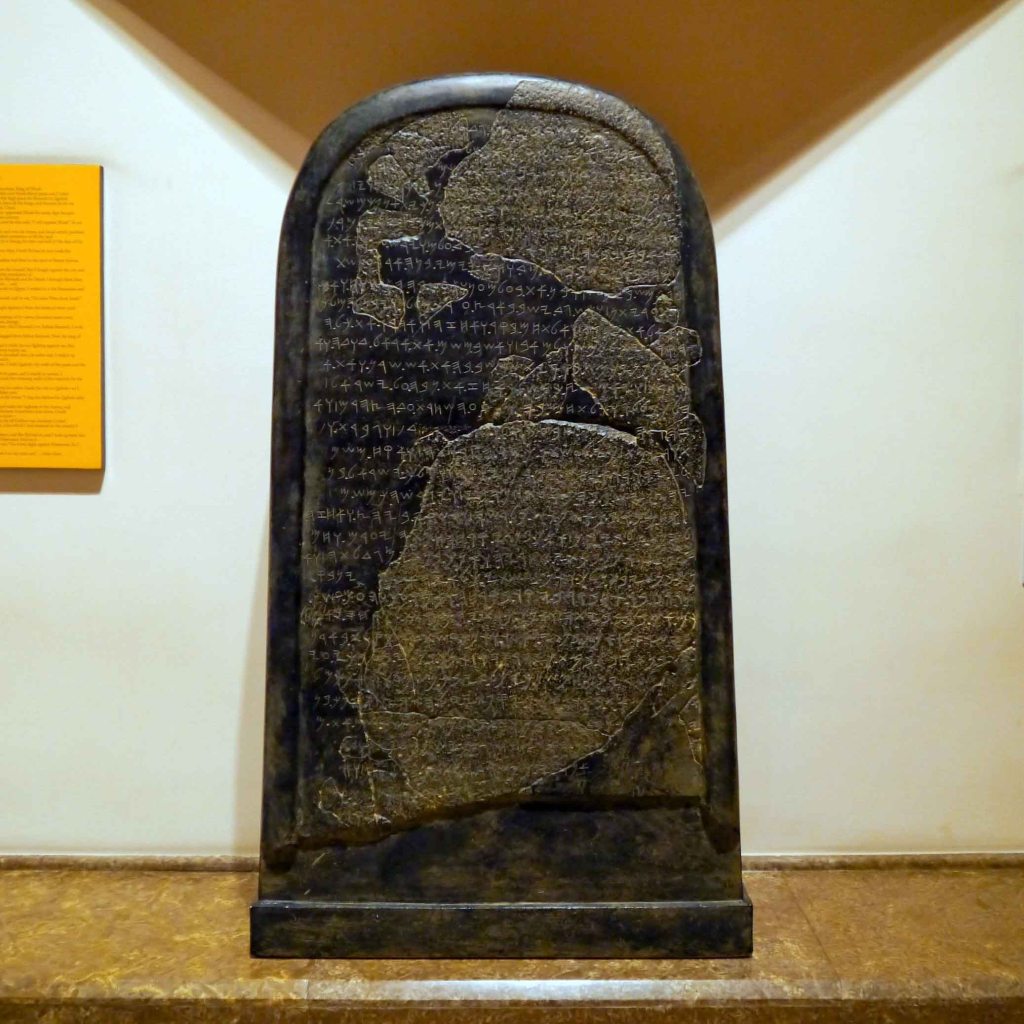

Adding another layer of historical depth is a replica of the Mesha Stele, an inscribed basalt monument from the 9th century BC. Discovered in Dhiban (modern-day Jordan), the stele records the military campaigns and construction achievements of King Mesha of Moab. It also contains one of the earliest known references to the Kingdom of Israel, making it a cornerstone of biblical archaeology and a vital artifact for understanding the political landscape of the Iron Age Levant. Although the original stele – now housed in the Louvre Museum in Paris – is fragmented, its inscription has significantly shaped the study of both biblical texts and ancient Near Eastern history.

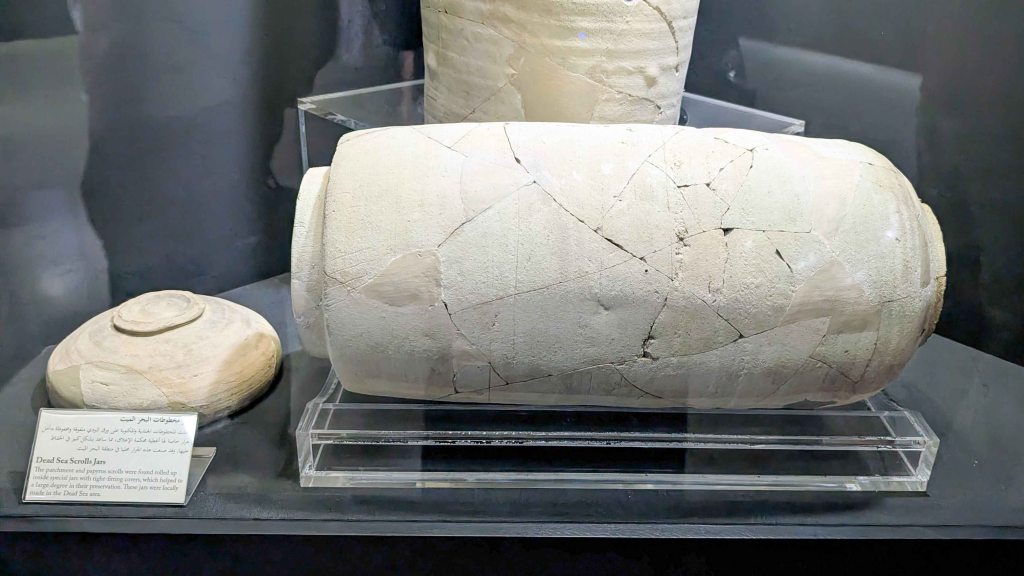

Equally fascinating is the museum’s rare exhibit of the Copper Scroll – one of the most enigmatic texts among the Dead Sea Scrolls, a collection of ancient Jewish manuscripts discovered over a ten-year period between 1946 and 1956 in the Qumran Caves along the northwestern shore of the Dead Sea. Unlike the majority of scrolls – typically written on leather or papyrus and focused on religious content – the Copper Scroll was engraved on thin metal sheets and contains no theological material. Dating to the 1st century AD and written in a variant of Mishnaic Hebrew, it lists over sixty locations purportedly concealing vast hoards of gold, silver, and temple treasures across the Near East. Some interpretations estimate these hidden riches total more than 160 tons. However, the wording of the scroll – inscribed on a strip just 1 millimeter thick and 2.4 meters long – is vague and geographically unspecific, leaving scholars divided over its meaning and credibility. Nonetheless, it has fueled decades of academic debate, treasure hunts, and conspiracy theories. Due to severe oxidation, archaeologists had to cut the scroll into 23 strips to read its contents, making it one of the most physically unique ancient texts ever recovered. To this day, none of the caches described in the Copper Scroll have been conclusively located, adding an enduring aura of mystery to this already extraordinary artifact.

King Abdullah I Mosque

Located just beyond Downtown Amman, the King Abdullah I Mosque stands as the city’s most impressive modern Islamic monument and one of its most recognizable landmarks. Completed in 1990, the mosque was commissioned by King Hussein (reign: 1952–1999) to honor the memory of his grandfather, King Abdullah I (reign: 1946–1951), the founder and first monarch of modern Jordan. King Abdullah I played a pivotal role in establishing the Hashemite Kingdom following the end of the British Mandate and the independence of Transjordan in 1946. His assassination in 1951 at Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem – while attending Friday prayers – marked a tragic chapter in Jordan’s early history, rooted in the broader regional turmoil surrounding the creation of Israel and the unresolved Palestinian issue.

The mosque’s most striking feature is its massive blue dome, which rises prominently to a height of 35 meters and is visible from many parts of the city. Adorned with bold turquoise and indigo geometric patterns, the dome represents a modern interpretation of classical Islamic design, symbolizing the unity and infinitude of God. Beneath it lies Amman’s largest prayer hall, capable of accommodating up to 7,000 worshippers. The structure seamlessly blends traditional Islamic architecture – notably Ottoman and Mamluk influences – with contemporary engineering, creating a space that feels both rooted in heritage and distinctly modern. The mosque’s octagonal interior is spacious and filled with natural light, creating an atmosphere of serenity and contemplation. Elegant white marble walls are inscribed with Quranic calligraphy, while intricate arabesque patterns embellish the mihrab and surrounding surfaces. Large crystal chandeliers, suspended from the soaring ceiling, add a touch of grandeur and complement the mosque’s minimalist color palette of white, gold, and blue.

Adjacent to the main building is a small but insightful Islamic Museum, which provides deeper context to Jordan’s Islamic heritage. The museum features a diverse collection of artifacts, including rare manuscripts, early Islamic coins, photographs of Amman’s religious history, and examples of decorative arts such as ceramic tiles, embroidered garments, and calligraphic panels. Together, the mosque and museum underscore the enduring influence of Islam on Jordan’s cultural and political identity, while also embodying the nation’s ongoing efforts to honor tradition and embrace modernity.

Sources

https://international.visitjordan.com

https://international.visitjordan.com/Wheretogo/Amman

https://www.jordanmuseum.jo/