The Ultimate Jordanian Road Trip is a nine-day exploration that weaves together Jordan’s most captivating historical, cultural, religious and natural landmarks.

Embarking on a journey through Jordan is like turning the pages of a living history book, where every landscape tells a story and every stone bears witness to civilizations long past. The adventure begins in Amman, the vibrant capital layered with millennia of history, where ancient ruins meet modern skylines. From there, travelers venture north to Jerash, the best-preserved Roman city in the region, and Ajloun Castle, an imposing Ayyubid fortress built to defend against Crusader incursions. The exploration then turns eastward to the Umayyad desert castles – Qasr al-Azraq, Qusayr ‘Amra, and Qasr al-Harranah – before heading west toward the Holy Land sites of Madaba and Mount Nebo, where intricate mosaics and sacred traditions bring biblical history to life. Descending to Earth’s lowest point, visitors arrive at the Dead Sea, renowned for its mineral-rich waters, dramatic landscapes, and deep biblical associations. The journey continues south to the imposing Crusader castles of Karak and Shobak, architectural testaments to centuries of conflict and cultural exchange. The highlight of the trip is Petra, the legendary Nabataean capital carved from rose-red sandstone cliffs – a wonder of the ancient world that continues to inspire awe. The adventure culminates amid the dramatic desert landscapes of Wadi Rum, a realm of surreal beauty immortalized by Lawrence of Arabia. Finally, the coastal city of Aqaba, where Jordan meets the Red Sea, offers a tranquil and fitting conclusion to this unforgettable voyage. Together, these destinations form an immersive journey through Jordan’s history, faith, and natural beauty – a reflection of the nation’s timeless role as a bridge between worlds.

| Attractions | Accommodation | |

|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | Amman | Amman |

| Day 2 | Jerash Archaeological Site Ajloun Castle | Amman |

| Day 3 | Desert Castles: Qasr al-Azraq, Qusayr ‘Amra, and Qasr al-Harranah Holy Land Sites: Madaba Mosaic Map and Mount Nebo | Amman |

| Day 4 | Dead Sea Floating Experience | Dead Sea |

| Day 5 | Crusader Castles: Kerak Castle and Shobak Castle | Wadi Musa |

| Day 6-7 | Petra: Main Trail, Petra Museum, Petra by Night Ad-Deir Hiking, High Place of Sacrifice Hiking, Little Petra | Wadi Musa |

| Day 8 | Wadi Rum: Desert Safari, Stargazing | Wadi Rum Bedouin Camp |

| Day 9 | Aqaba: Diving in the Red Sea | Aqaba |

Day 1 – Amman

Built upon the foundations of ancient civilizations and shaped by millennia of cultural exchange, conquest, and adaptation, Amman has evolved into a dynamic urban landscape where Roman theatres stand beside bustling markets, and Umayyad ruins overlook glass towers and contemporary cafes. The city embodies the continuity of tradition amid constant reinvention in response to changing political and cultural tides.

Spread across a series of steep hills known as jebels, Amman has witnessed continuous human settlement since the Neolithic period, making it one of the oldest continuously inhabited places in the region. By the 13th century BC, the area was known as Rabbath Ammon, the capital of the Ammonite Kingdom. Situated along the King’s Highway – an ancient trade route connecting Egypt with Mesopotamia – the city prospered from commercial traffic and the wealth it generated. Over time, Amman came under the control of powerful empires. It was conquered by the Neo-Assyrians in the 8th century BC, followed by the Neo-Babylonians in the 6th century BC, and later the Achaemenid Persians – each leaving a distinct mark on its urban landscape and political structure. During the Hellenistic period, the region came under the control of the Ptolemies, and the city was renamed Philadelphia in honor of Pharaoh Ptolemy II Philadelphus (reign: 284–246 BC). Under this new name and Hellenistic influence, Philadelphia flourished – marked by Greek-style architecture, administrative reforms, and vibrant cultural exchange. Following Roman annexation in 63 BC, the city experienced a surge in urban development and monumental construction, traces of which still grace modern Amman: the grand Roman Theatre, the Nymphaeum, and the Temple of Hercules atop Jebel al-Qal’a.

During the early Islamic period, the city once again rose to prominence. The Umayyads built a palace complex atop Jebel al-Qal’a in the 8th century, recognizing its enduring strategic value. Following the decline of the Umayyad Caliphate, however, the city gradually faded into obscurity, becoming little more than a scattering of ruins for centuries. Amman’s modern resurgence began in the early 20th century, amid the geopolitical reshaping of the Middle East following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. In 1921, the Hashemite Emir – and later King – Abdullah I (reign: 1946-1951) designated Amman as the capital of the newly formed Emirate of Transjordan, which became the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan in 1950. At the time, Amman was still a modest village with a population of only a few thousand and limited infrastructure. But it quickly emerged as the political, economic, and cultural center of the nascent Jordanian state. Throughout the 20th century, the city expanded rapidly – driven by waves of migration, urbanization, and regional conflict. This demographic transformation infused Amman with diverse cultural influences while also placing considerable strain on its infrastructure and housing.

Today, Amman is a vibrant and multifaceted metropolis – a city of contrast, where sleek glass towers and modern shopping malls rise above ancient ruins, and where centuries-old traditions coexist with cosmopolitan modernity It stands as a living bridge between the country’s storied past and its aspirations for the future, embodying the resilience and adaptability that have shaped the nation’s journey through history.

Day 2 – Jerash and Ajloun Castle

Inhabited since the Bronze Age, the Jerash Archaeological Site stands today as one of the most spectacular and best-preserved Roman-era cities in the Middle East. Nestled in a fertile valley surrounded by olive-covered hills, Jerash’s prosperity was shaped by both its geography and history. Strategically located along the ancient King’s Highway – a vital trade artery linking Egypt with Mesopotamia – the city flourished as a hub of commerce, culture, and craftsmanship.

During the Hellenistic period of the 3rd century BC, Jerash emerged as a thriving urban center known as Gerasa, likely founded by the Seleucids. In the 1st century BC, it became one of the ten cities of the Decapolis League – a federation of self-governing, Hellenized towns on the eastern frontiers of the Roman Empire, united by shared economic and cultural interests. Gerasa gained considerable prestige from its civic autonomy, monumental architecture, and cosmopolitan population. Under Emperor Trajan (reign: 98–117 AD), Gerasa lost its independent status, but this transition ultimately ushered in an era of unprecedented prosperity. Trajan’s annexation of the Nabataean Kingdom and its capital, Petra, in 106 AD integrated regional trade routes more firmly into the Roman network. Wealth poured into Gerasa, fueling an ambitious building program that transformed it into one of the grandest provincial centers of the empire. The reign of Emperor Hadrian (reign: 117–138 AD) brought further embellishments, including monumental gates and public works constructed to commemorate his visit to the city in 129 AD.

After a period of decline in the 3rd century, Gerasa experienced a renaissance under the Byzantine Empire, as Christianity spread throughout the region. By the 5th and 6th centuries, numerous churches had been built, many incorporating reused Roman columns and stones. These early Christian structures, richly adorned with intricate mosaic floors, provide valuable insight into the evolution of Byzantine ecclesiastical architecture in the Levant. The city continued to flourish under the Umayyad Caliphate in the 7th and early 8th centuries, maintaining its prominence as a regional center. However, in 749 AD, a devastating earthquake originating in Galilee destroyed much of Jerash and its surroundings. Subsequent tremors, shifting trade routes, and political instability led to further decline. By the time of the Crusades, Jerash had become a shadow of its former self, and in 1112, it was sacked by Baldwin II, King of Jerusalem (reign: 1118–1131). Over the centuries, the once-thriving city fell into ruin, its monuments gradually buried under layers of silt and sand, only to be rediscovered and excavated in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Today, Jerash offers visitors a remarkable journey through time. Entry to the site is through the Arch of Hadrian, built in honor of the emperor’s visit. Nearby stands the Hippodrome, where chariot races and athletic contests once thrilled cheering crowds. Beyond lies the South Gate, part of the 4th-century city walls, leading into the heart of ancient Gerasa. To the left rise the Temple of Zeus – dedicated to the chief deity of the Greek pantheon – and the grand South Theatre, which once seated more than 3,000 spectators and is still occasionally used for performances today. One of Jerash’s most distinctive landmarks is the Oval Plaza (1st century AD), an architectural rarity unique in the ancient world. Measuring roughly 80 by 90 meters, this asymmetrical open space is encircled by 160 Ionic columns and paved with limestone blocks laid over a sophisticated drainage system. From here stretches the Cardo Maximus, the city’s main north-south thoroughfare – a 600-meter-long colonnaded street lined with public buildings, shops, and residences. Deep grooves in the paving stones mark the ruts left by ancient chariots. To the west lies the Agora, once the bustling food market of Gerasa, complete with a central fountain. At the Tetrapylon, the Cardo intersects with the South Decumanus, an east-west street that connected other key parts of the city. Further north stands the Nymphaeum, a richly ornamented 2nd-century public fountain dedicated to the water nymphs, featuring a carved basin with a charming design of four fish kissing. Continuing along the Cardo brings visitors to the remains of an Umayyad Mosque, followed by the smaller but well-preserved North Theatre. Nearby stands the impressive Temple of Artemis, dedicated to the goddess of the hunt, wilderness, and fertility – the patron deity of Gerasa. The temple’s Corinthian columns still tower dramatically over the site, and visitors can experience a curious phenomenon: when gently pushed, the columns appear to sway ever so slightly, a testament to the ancient engineers’ precision. Close to the Temple of Artemis lie several Byzantine churches, including the renowned Complex of the Three Churches (526–533 AD), distinguished by beautifully preserved mosaic floors depicting vines, animals, and Christian symbols.

Nestled atop a green hill, Ajloun Castle – also known as Qal’at ar-Rabad – stands as one of the most remarkable examples of Arab military architecture in the Middle East. Overlooking the Jordan Valley, this imposing medieval fortress has witnessed centuries of conflict, conquest, and cultural transformation. Its powerful walls and commanding presence continue to tell the story of a region that has long been a crossroads of civilizations, faiths, and empires.

Ajloun Castle was constructed on the site of a Byzantine-era monastery, remnants of which were discovered during archaeological excavations. The fortress was built in 1184 by Izz al-Din Usama, a general and nephew of Salah ad-Din (Saladin), the formidable Sultan of Egypt and Syria (reign: 1174–1193). This period was marked by the Crusades, a series of military campaigns launched by European powers to capture the Holy Land. Saladin’s forces sought to defend Muslim territories and strengthen their hold over key routes and strategic points across the Levant. Standing 1,200 meters above sea level, Ajloun Castle commands sweeping views of the Jordan Valley and the surrounding mountains. This vantage point allowed it to control movement along the vital trade and pilgrimage routes linking Syria with southern Jordan and Egypt. The castle also served as a watchtower, guarding the passage between Damascus and Aqaba. It was also part of a defensive network that operated in coordination with other fortresses such as Karak and Shobak.

Constructed primarily from local limestone, the fortress was originally built with four corner towers, a drawbridge, and arrow slits that allowed archers to fire at enemies while remaining shielded from attack. The design combined elegance with practicality: its thick walls, narrow corridors, and sloped passageways were all intended to slow invaders and protect defenders during sieges. Over the centuries, the castle was expanded and modified to adapt to new military technologies and shifting political conditions. During the Mamluk period (13th–16th centuries), additional towers were constructed, and fortifications were strengthened to accommodate larger garrisons and more advanced weaponry such as catapults and trebuchets. Inside, the castle featured living quarters, storage rooms, cisterns, and stables, all carefully designed to support the needs of soldiers during long periods of isolation. However, with the decline of regional conflicts and the rise of Ottoman control, Ajloun Castle gradually lost its military importance. Natural disasters, including several earthquakes, inflicted significant damage – particularly during the 1837 and 1927 tremors – but major restoration efforts have since stabilized and preserved the structure for future generations.

Today, Ajloun Castle is one of Jordan’s most visited historical landmarks and a powerful symbol of national heritage and identity. Visitors can wander through its stone staircases, vaulted chambers, and labyrinthine passageways, experiencing firsthand the ingenuity and practicality of medieval engineering. Inside the castle, a museum showcases artifacts uncovered during excavations, including ceramics, coins, weapons, and tools from the Ayyubid and Mamluk periods, helping visitors understand the daily life of soldiers, the castle’s defensive systems, and its role in regional history. Its commanding hilltop location surrounded by lush olive groves and pine forests offers breathtaking panoramic views of the Jordan Valley, the Dead Sea, and even the hills of Galilee on clear days. Surrounded by lush olive groves and pine forests, the castle offers breathtaking panoramic views of the Jordan Valley, the Dead Sea, and even the hills of Galilee on clear days.

Day 3 – Desert Castles and Holy Land Sites

Dating from the 7th-8th centuries, the desert castles, or qasrs, are fortified palaces built primarily by the Umayyad dynasty. Scattered across the eastern desert plains, Jordan’s desert castles – most notably Qasr al-Azraq, Qusayr ‘Amra, and Qasr al-Harranah – stand among the most prominent architectural and historical monuments of the early Islamic period. These remarkable structures demonstrate the Umayyads’ ingenuity in blending functionality with artistry, combining defensive design with luxurious interiors, and adapting to the challenges of the harsh desert environment.

Although referred to as “castles” because of their imposing appearance and fortified walls, these structures served a variety of purposes beyond mere defense. Some functioned as residences or rest houses for travelers and traders journeying along the caravan routes connecting Egypt with Mesopotamia, while others operated as administrative centers, hunting lodges, or agricultural estates. They also fulfilled symbolic and political roles, asserting Umayyad authority over the sparsely populated desert regions and strengthening ties with local Bedouin tribes. Architecturally, a typical desert castle was designed as a self-contained compound, consisting of a main residential complex surrounded by auxiliary structures such as water reservoirs, storage rooms, stables, olive presses and grinding mills, hammams [bathhouses], and sometimes a mosque, all enclosed within protective walls. Many castles were constructed near a wadi or seasonal watercourse, ensuring access to water in the arid landscape. These desert castles reflect a charming blend of Islamic, Byzantine, and Persian architectural influences, revealing the multicultural nature of the Umayyad Caliphate. Many were richly decorated with frescoes, mosaics, and stucco reliefs that portrayed both secular and symbolic themes. The artistic detail found in these buildings demonstrates a refined aesthetic that challenges the misconception of early Islamic art as purely aniconic. Standing in solitude amid the vast desert, the qasrs evoke an aura of mystery, power, and refinement – embodying the Umayyads’ vision of dominion, sophistication, and harmony between nature and culture.

Among these remarkable monuments, Qasr al-Azraq holds a particularly prominent place in Jordan’s cultural heritage. Constructed primarily from black basalt stone, it immediately distinguishes itself by its dark, striking appearance and its location at an ancient oasis – the only permanent water source in a vast stretch of desert. This oasis made the site vital for travelers, traders, and armies moving across the arid expanse between Mesopotamia and Egypt. The Romans were the first to fortify the area, recognizing its strategic importance, and the Umayyads later expanded and adapted it into a military and administrative stronghold. In the 13th century, the Ayyubids redesigned and reinforced Qasr al-Azraq, giving it much of the form that remains today. The fortress’s massive stone walls, heavy basalt doors, and geometric design emphasize its defensive character. Beyond its military role, the site gained lasting fame for its association with the Arab Revolt (1916-1918), when T. E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia) and the Arab forces used the castle as their base during the winter of 1917-1918.

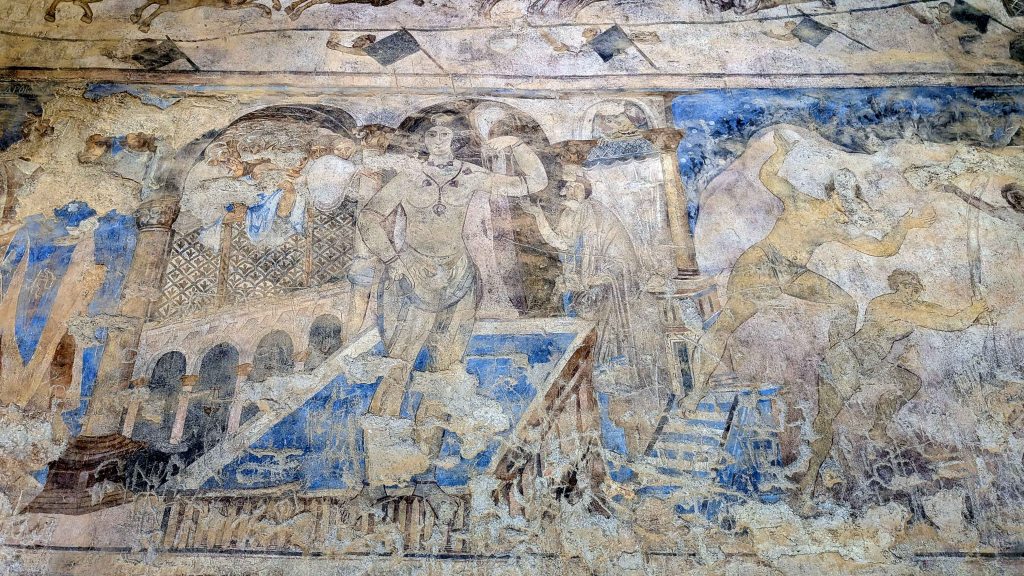

Equally fascinating is Qusayr ‘Amra, one of the most celebrated and historically significant Umayyad desert castles. Built as a royal retreat and bathhouse, it provided rest and recreation for members of the Umayyad elite. Although modest in scale compared to other castles, Qusayr ‘Amra is world-renowned for its exceptional frescoes, which adorn its walls and ceilings. These paintings depict vivid scenes of royal banquets, hunting expeditions, musicians, animals, mythological creatures, and celestial imagery – offering a rare glimpse into the art leisure, and worldview of the early Islamic elite. Particularly striking are the human and semi-nude figures, imagery that would later become inconceivable in Islamic art. The domed ceiling of the caldarium (the hot room of the bathhouse) features a celestial map of the constellations, regarded as one of the earliest examples of astronomical art in Islamic architecture. Constructed from limestone and basalt, the building reflects a harmonious synthesis of Roman, Byzantine, and Islamic influences, especially evident in its bathhouse layout, which closely resembles the Roman thermae. Recognized for its outstanding historical and artistic significance, Qusayr ‘Amra was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1985.

Another architectural masterpiece, Qasr al-Harranah – also known as Qasr Kharana – is among the most striking examples of early Umayyad architecture. Built primarily from local limestone and sandstone, the castle features a square layout with corner towers and a central courtyard, giving it the appearance of a fortress. However, scholars widely agree that it was not designed primarily for military defense as its lacks essential defensive features such as a reliable water source or strategic positioning. Instead, Qasr al-Harranah likely served as a resting place or meeting venue for travelers, traders, and local Bedouin leaders. Its arched ceilings, decorative niches, and Arabic inscriptions reveal a sophisticated fusion of Roman, Persian, and Islamic architectural traditions, illustrating the cultural diversity and interconnectedness of the early Islamic world. Despite centuries of exposure to the elements and occasional restorations following natural wear and invasions, Qasr al-Harranah remains remarkably well-preserved – a silent yet powerful testament to the resilience and craftsmanship of its builders.

Western Jordan is home to some of the most sacred and historically significant sites in biblical tradition. The country’s rugged hills, fertile valleys, and sweeping desert plateaus form a landscape deeply intertwined with stories that hold profound meaning for the three major Abrahamic religions – Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Among its most notable sacred sites are Madaba, home to the oldest known cartographic depiction of the Holy Land, and Mount Nebo, revered as the place where Moses gazed upon the Promised Land before his death.

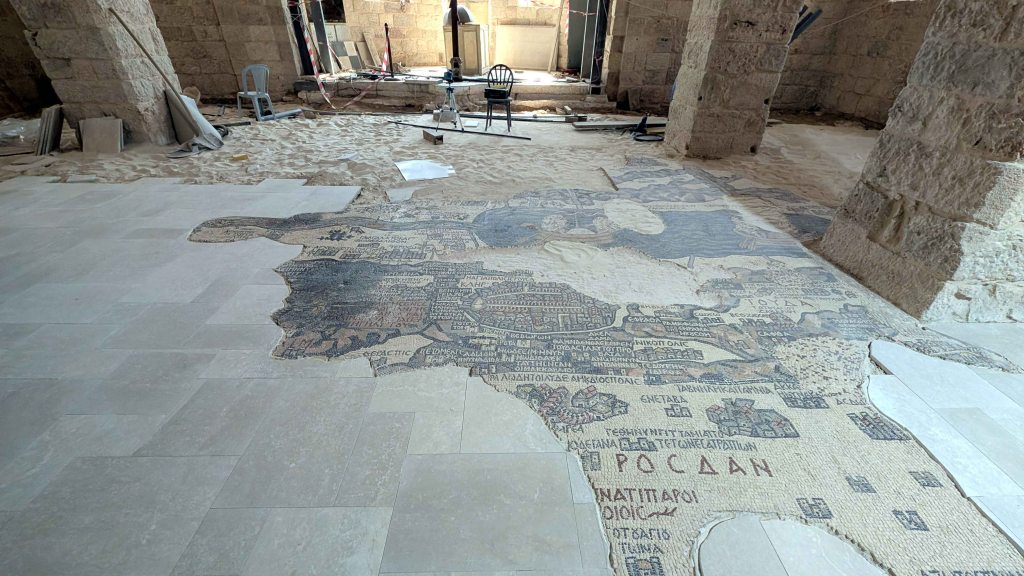

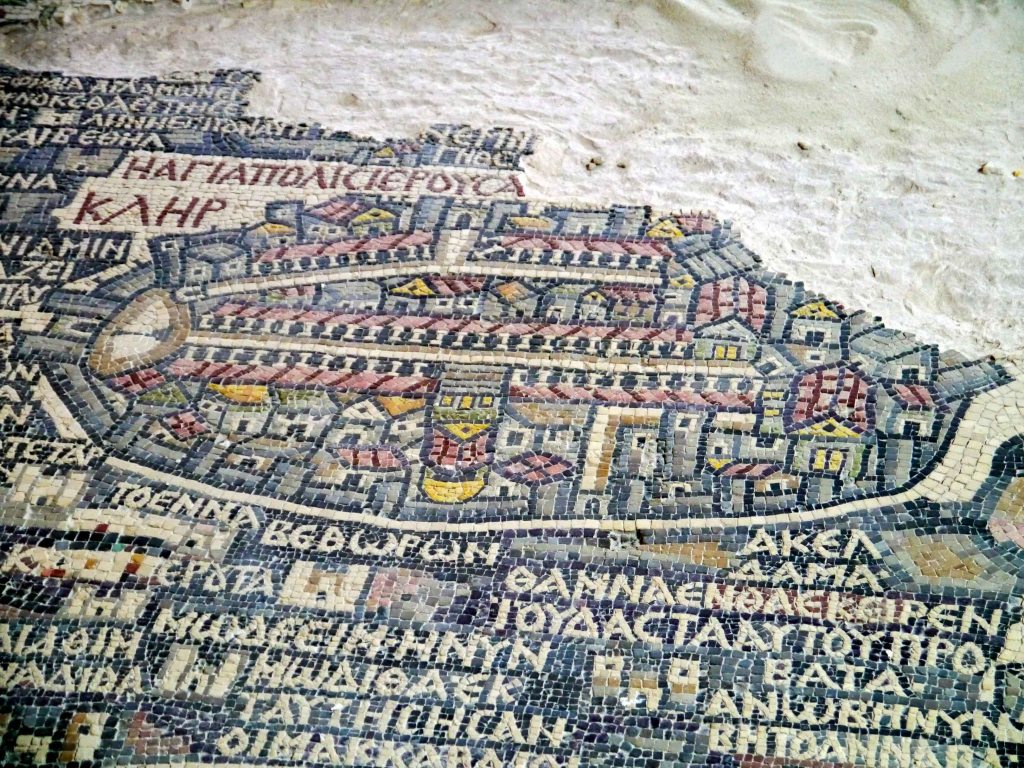

The Madaba Mosaic Map,set into the floor of St. George’s Greek Orthodox Church in the town of Madaba, is one of the most remarkable archaeological and religious artifacts from the early Byzantine era. Revered as the oldest known original cartographic representation of the Holy Land, it offers a rare and invaluable glimpse into the biblical and geopolitical landscape of antiquity. Likely created during the reign of Emperor Justinian (reign: 527–565 AD), at the height of the Byzantine period, the map originally measured an impressive 21 by 7 meters, covering a large section of the church’s nave. Although much of it has been damaged by time, iconoclasm, and later construction, about a quarter of the original mosaic survives. Even in this incomplete state, the Madaba Map remains the most detailed and earliest surviving visual depiction of the biblical world.

Unconventionally, the map is oriented east–west, diverging from the north–south orientation typical of modern maps. The surviving portion spans a vast geographical area – from Lebanon in the north to the Nile Delta in the south, and from the Mediterranean Sea in the west to the Eastern Desert in the east. More than 150 place names and geographical features are labeled in ancient Greek, including rivers, mountains, towns, and villages. The level of detail is extraordinary: the Jordan River is shown teeming with fish; the Dead Sea contains boats transporting salt and grain; and the Mountains of Sinai are depicted as a natural boundary separating barren desert from the fertile Nile lands. Cities like Jericho appear as fortified enclosures with towers, while Bethlehem is clearly marked, dominated by the Church of the Nativity. At the very center of the map lies Jerusalem, presented as a thriving Byzantine city, complete with the Damascus Gate, the colonnaded Cardo Maximus, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre topped by a golden dome, and the Tower of David. This central representation underscores the map’s likely role as a pilgrimage aid, intended to help Christian travelers navigate the Holy Land and better understand the geography of the scripture.

Beyond its religious function, the Madaba Mosaic Map holds immense historical and academic value. It provides critical insight into Byzantine cartography, urban planning, and Christian sacred geography. Its accurate positioning of ancient towns and landmarks has helped modern archaeologists and historians identify and confirm numerous biblical and classical sites, many of which had been forgotten or misidentified for centuries.

Mount Nebo is one of Jordan’s most significant biblical and historical landmarks, renowned for both its spiritual symbolism and panoramic vistas. Perched high above the Jordan Valley, the site offers breathtaking views that stretch across the Dead Sea, the Jordan River, and – on particularly clear days – even as far as Jericho, Jerusalem, and the hills of Bethlehem.

According to tradition, this is the place where Moses ascended from the plains of Moab and was granted a divine vision of the Promised Land, which he was not permitted to enter. Although Moses is believed to have died and been buried somewhere nearby, the exact location of his tomb remains unknown, adding to Mount Nebo’s sacred mystique. Christian veneration of the site began early. In the 4th century, during the reign of Emperor Constantine (reign: 306–337 AD), a sanctuary was built on the mountain to honor the memory of Moses. This marked the beginning of pilgrimage to Mount Nebo, making it one of the earliest such destinations in the Holy Land. Over the centuries, the site evolved into a monastic complex, reflecting its growing religious and spiritual importance.

Since the 1930s, Mount Nebo has been cared for by the Franciscan Order, which has undertaken extensive archaeological excavations and conservation efforts to preserve its historical and artistic treasures. The site is particularly famous for its early Byzantine mosaics, among the finest in the region. These intricate works vividly depict scenes of daily life – including hunting, agriculture, and animal husbandry – alongside symbolic Christian motifs, showcasing the artistic and spiritual richness of the monastic community that once flourished there. Today, Mount Nebo remains a revered pilgrimage destination for followers of all three major Abrahamic religions – Judaism, Christianity, and Islam – much like St Catherine’s Monastery in Sinai, Egypt. It has been visited by numerous prominent religious leaders, most notably Pope John Paul II during his 2000 pilgrimage to the Holy Land.

Day 4 – Dead Sea

The Dead Sea – which is actually a lake rather than a sea – stands as one of Jordan’s most extraordinary natural and historical landmarks.

Situated at more than 400 meters below sea level, it holds the title of the lowest point on Earth. The Dead Sea is also one of the saltiest bodies of water in the world, with a salinity nearly ten times greater than that of the ocean, giving it a density of about 1.24 kg/liter. This remarkable density allows swimmers to float effortlessly on its surface, an experience unique to this otherworldly environment. The high salinity renders the lake inhospitable to most plant and animal life, which explains its name. The mineral-rich waters and therapeutic mud of the Dead Sea, abundant in magnesium, sodium, potassium, bromine, and other trace elements, have been prized since antiquity for their healing and cosmetic properties. Ancient Egyptian, Greek, and Roman civilizations valued these minerals for use in embalming, medicine, and beauty treatments – and even Queen Cleopatra is said to have sought the Dead Sea’s minerals for her skincare. The area’s oxygen-rich atmosphere, containing higher levels of oxygen than most other places on Earth, further enhances its reputation as a site of rejuvenation and health. Beyond its therapeutic appeal, the Dead Sea has long held economic and cultural importance. In ancient times, its naturally occurring free-floating bitumen was harvested and used in Egyptian mummification, while in modern times, the lake’s mineral wealth continues to be tapped for potash and bromine used in fertilizers. However, despite its enduring significance, the Dead Sea faces a serious environmental crisis. Over the past century, its water level has dropped by more than 12 meters, largely due to the diversion of water from the Jordan River, its main tributary, for agricultural and domestic use. The shrinking shoreline has also led to the formation of hundreds of sinkholes, highlighting the urgent need for regional cooperation and conservation efforts to preserve this unique ecosystem for future generations.

To the east of the Dead Sea rise the Mountains of Moab, offering dramatic scenery and natural wonders. Among these is Hammamat Ma’in [Ma’in Hot Springs], located about 264 meters below sea level. Nestled within a lush canyon, this oasis of mineral-rich hot springs and cascading waterfalls is fed by rainwater that seeps deep into the Earth, where it is heated by geothermal activity before reemerging at the surface. With temperatures reaching up to 63°C, the springs have long been regarded as a natural remedy for arthritis, circulatory disorders, and various skin conditions. Further south, the Wadi Mujib Nature Reserve descends through towering sandstone cliffs to the shores of the Dead Sea, creating a striking contrast between rugged desert and flowing water. Carved over millennia by the Mujib River, the wadi features narrow gorges, hidden waterfalls, and emerald pools. It is also a vital ecological sanctuary, home to wildlife including the Nubian ibex, red fox, and more than 300 species of migratory birds. The reserve offers some of Jordan’s most thrilling hiking and canyoning adventures, where visitors can wade through streams, scramble up rocks, and rappel down waterfalls.

The area surrounding the Dead Sea is steeped in biblical tradition, forming one of the most spiritually resonant landscapes in the world. According to the Book of Genesis, it was near here that the cities of Sodom and Gomorrah were destroyed and that Lot and his family fled, with Lot’s wife famously turned into a pillar of salt. Adding to the region’s rich cultural and historical landscape is the Museum at the Lowest Place on Earth, located near the southern end of the Dead Sea. Though modest in size, the museum houses an impressive collection of archaeological artifacts, including items from Lot’s Cave, ancient Graeco-Roman textiles, and numerous Greek inscriptions. Lot’s Cave, situated just above the museum, is believed to be the refuge where Lot and his daughters sought safety after fleeing Sodom. During the Byzantine period, the site was converted into a church, and visitors today can still see the intricate mosaic floor and the remains of the ancient structure. A short distance to the north lies the Baptism Site of Jesus Christ, known as Bethany Beyond the Jordan, one of Christianity’s holiest locations and the site where John the Baptist is believed to have baptized Jesus in the waters of the Jordan River. High above the eastern shore stands the Fortress of Machaerus, traditionally identified as the place where John the Baptist was imprisoned and executed around 30 AD at the request of Salome. The region is equally renowned for the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls – a collection of ancient Jewish manuscripts found between 1946 and 1956 in the Qumran Caves along the northwestern shore. These texts, dating from the 3rd century BC to the 1st century AD, include some of the earliest known biblical writings and have profoundly shaped modern understanding of Judaism and early Christianity.

Day 5 – Crusader Castles

Jordan is home to several remarkable Crusader castles – powerful reminders of the turbulent medieval era when European Crusaders and Muslim dynasties vied for control over the Holy Land. Built between the 12th and 13th centuries, these fortresses – most notably Karak Castle and Shobak Castle – were strategically positioned along key trade and pilgrimage routes. They served not only as military strongholds but also as administrative centers and enduring symbols of power.

Karak Castle is one of the most formidable and well-preserved Crusader fortresses in the Levant. Perched dramatically atop a ridge commanding sweeping views of the surrounding valleys, the castle served as a major stronghold in the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem. Construction began in 1142 under Pagan the Butler, the Frankish lord of Transjordan, who had been granted control of the region by King Baldwin II of Jerusalem (reign: 1118–1131). Strategically located east of the Dead Sea, Karak formed part of a chain of fortifications stretching from Jerusalem to Aqaba, built to defend the kingdom’s eastern frontier. Its elevated position allowed the Crusaders to monitor Bedouin movements, secure vital trade routes linking Damascus, Mecca, and Cairo, and guard against incursions from the Muslim east.

The castle’s most infamous occupant was Raynald of Châtillon (reign: 1176–1187), a reckless and provocative nobleman, who seized control of Karak in 1176. Known for his audacious and often brutal exploits, Raynald repeatedly attacked Muslim caravans passing through the region and even plotted a direct assault on Mecca – an unforgivable provocation that earned him the wrath of his enemies. In retaliation, Salah ad-Din (Saladin), the formidable Sultan of Egypt and Syria (reign: 1174–1193), vowed to eliminate Raynald and reclaim Crusader-held territories. He launched two prolonged sieges of Karak Castle, in 1183 and 1184, though both ultimately failed due to the fortress’s formidable defenses and timely Crusader reinforcements. Following his decisive victory at the Battle of Hattin in 1187, however, Saladin reasserted Muslim dominance over the Holy Land, recapturing Jerusalem and most other Crusader strongholds. Karak Castle finally fell to his forces in 1188.

Architecturally, Karak Castle is a masterpiece of Crusader military architecture, blending Frankish design with later Byzantine and Islamic influences. The original Crusader sections, built of dark volcanic tufa, feature massive walls and robust towers, while later Ayyubid and Mamluk additions used lighter white limestone – a striking visual contrast that reflects the site’s layered history. The lower levels remain particularly well-preserved, inviting visitors to explore a labyrinth of vaulted halls, storerooms, kitchens, and stables that vividly evoke the hardships of medieval siege warfare. The extensive underground galleries, once used as shelters during attacks, were ingeniously designed for defense, with narrow arrow slits, maze-like corridors, and strongholds carved deep into the rock.

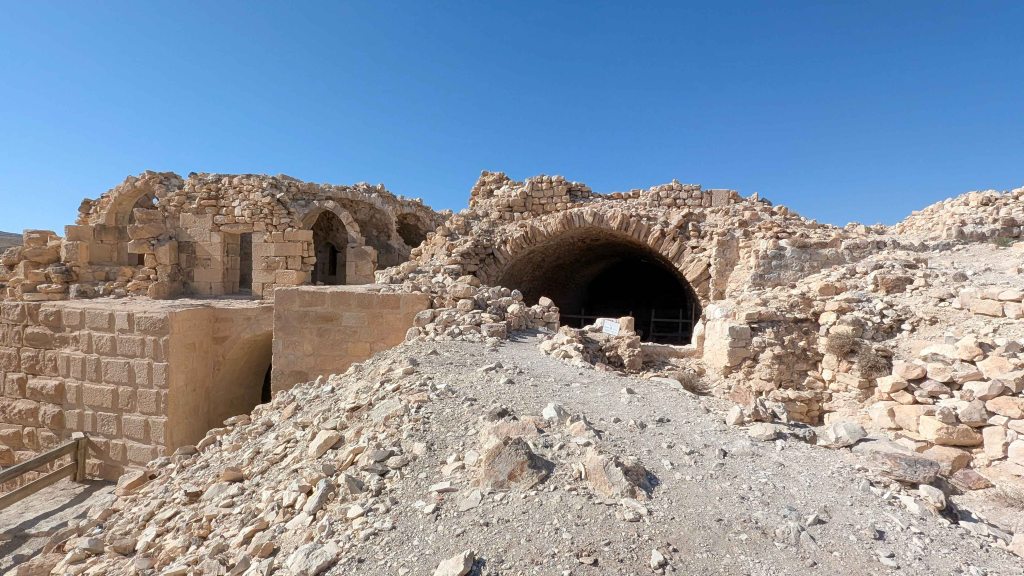

Shobak Castle, perched on a conical hill amid Jordan’s rugged southern landscape, commands a dramatic and solitary presence. Often observed only by passing flocks of sheep and goats, the fortress exudes an air of quiet endurance, standing as a weathered sentinel over the desolate terrain. Founded in 1115, by King Baldwin I of Jerusalem (reign: 1100–1118) – the first monarch of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem – Shobak was the first Crusader stronghold established east of the Jordan River. Strategically located to oversee both the pilgrimage routes to Mecca and the lucrative trade arteries connecting Damascus, Mecca, and Cairo, its construction marked a bold extension of Crusader influence into Transjordan. Like Karak, Shobak later came under the control of Raynald of Châtillon, who used it as a base for his aggressive raids deep into Muslim lands. Despite withstanding multiple assaults, the fortress ultimately surrendered in 1189 after a prolonged siege by Saladin’s forces.

Although time and warfare have reduced much of Shobak to ruins, the fortress still bears witness to its Crusader origins and strategic ingenuity. Surviving features include portions of the outer walls, rounded towers, arched gatehouses, and several vaulted chambers. Following its capture, Shobak was refurbished by the Ayyubids and later the Mamluks, who added inscriptions, architectural refinements, and a mosque within the compound. One of the castle’s most remarkable features is its hidden water system – a steep, rock-hewn tunnel of over 350 narrow, slippery steps that descends through the hillside to a freshwater spring outside the fortress walls. This concealed passage ensured a reliable water supply during sieges and remains an enduring testament to the engineering skill and resourcefulness of its builders.

Day 6-7 Petra

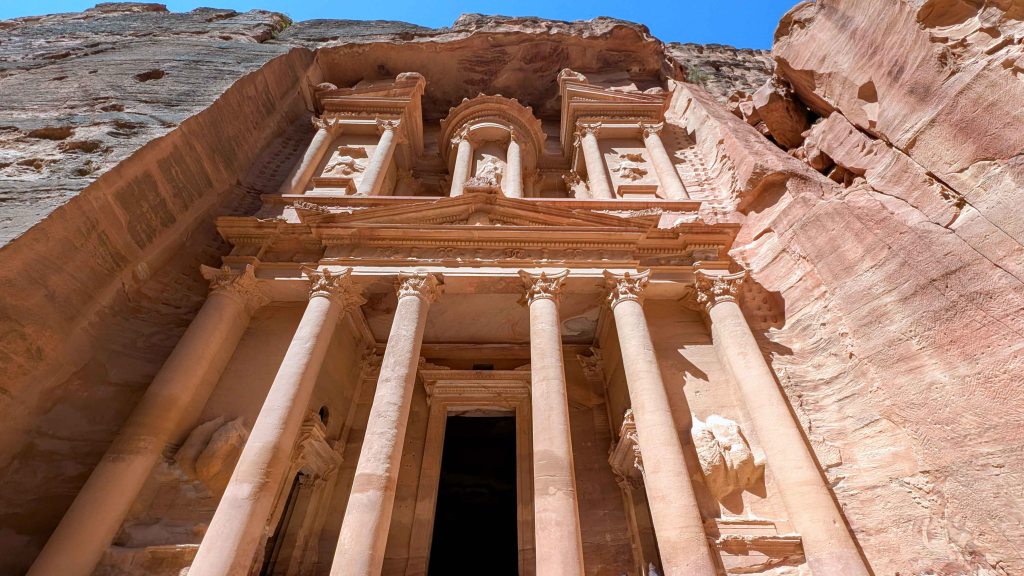

Petra is one of the world’s most awe-inspiring and atmospheric archaeological sites – the most iconic legacy of the ancient Nabataean civilization. In just two centuries, the Nabataeans transformed a barren wilderness into a vibrant and thriving metropolis. The tombs and temples carved into the dramatic sandstone cliffs remain enduring testaments to their architectural mastery, spiritual depth, and lasting imprint on the rugged desert landscape.

The Nabataeans, an ancient Arab people, began building Petra around the 4th century BC. Their decision to settle in such an arid, mountainous terrain demonstrated remarkable strategic foresight. Petra was located at the crossroads of major caravan routes, making itan ideal commercial hub for controlling and taxing the region’s vibrant trade network. Yet Petra’s geography offered more than just economic advantage. Spread across a vast plane, the city was naturally fortified by steep cliffs. In a desert where water was scarce, Petra held another crucial benefit: it lay at the confluence of several seasonal riverbeds, known as wadis, which provided access to vital water sources. Inevitably, Petra’s wealth and strategic location attracted the attention of the Roman Empire. Concerned by the rising power of the Nabataean Kingdom, Emperor Trajan (reign: 98–117 AD) annexed the territory in 106 AD. However, Petra’s prosperity began to wane as maritime trade routes gradually replaced overland caravan networks. This economic shift, combined with two devastating earthquakes in the 4th and 8th centuries AD, led to the city’s decline. By the early Islamic period, Petra had largely faded from historical records and was known only to local Bedouins.

Today, Petra is one of the most visited archaeological sites in the world. Designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1985, it is also a protected archaeological park and one of the New Seven Wonders of the World, attracting visitors from across the globe to its windswept valleys, crimson cliffs, and timeless monuments. While Petra’s most iconic landmarks – such as the Siq, Al-Khazneh [the Treasury], and the Royal Tombs – can be visited on a half-day tour, those who choose to linger are rewarded with a much deeper and more intimate experience. A full day allows for a comprehensive journey along Petra’s main trail, stretching from the Visitor Center to the sacred precinct of Qasr al-Bint [Palace of the Pharaoh’s Daughter], with ample time to explore the Royal Tombs and climb to either Ad-Deir [the Monastery] or the High Place of Sacrifice. With two or more days, the experience becomes truly immersive. Visitors can tackle both major hikes at a more relaxed pace, uncover lesser-known trails, and venture off the beaten path to discover hidden tombs, unexcavated ruins, and panoramic views rarely seen by day-trippers. An extended stay also provides the opportunity to visit nearby Siq al-Barid, commonly known as Little Petra – a smaller, more intimate Nabataean site that likely served as a caravanserai, offering lodging and provisions to traders traveling along the incense and spice routes. Not to be missed is Petra by Night, a rare and evocative way to experience the ancient Nabataean capital as it may have appeared to travelers centuries ago – bathed in candlelight beneath the quiet stillness of the desert night.

Day 8 – Wadi Rum

The desert landscape of Wadi Rum is one of the most iconic sights in the Middle East – a place where nature’s grandeur is shrouded in silent mystery. Towering ochre-colored sandstone and granite pinnacles, sculpted over millennia by wind, sand, and water into jagged, otherworldly shapes, rise up to 600 meters above the vast, sweeping valley floors. These dramatic formations emerge like islands from a sea of red and golden sand, creating a surreal, cinematic terrain so striking that it has often served as a stand-in for Mars and other alien worlds in major films.

Wadi Rum’s beauty is matched by its profound historical and cultural significance. Once a crucial junction on the ancient trade routes connecting southern Arabia with the Levant and the Mediterranean, the desert bears enduring traces of human habitation, including the remains of a Nabataean temple and ancient water channels. Scattered across its cliff faces and solitary boulders is a remarkable collection of rock art left by successive cultures over the centuries. Archaeologists have identified more than 25,000 petroglyphs and 20,000 inscriptions – mostly in Thamudic, Nabataean, and early Arabic – depicting human figures, camels, ibex, hunting scenes, and symbolic motifs, providing a silent yet powerful record of the region’s long human history. One notable site is Khazali Canyon, a steep, narrow gorge whose walls are richly inscribed with Thamudic texts and ancient graffiti.

Wadi Rum was brought to international attention by Thomas Edward Lawrence (1888–1935), the British army officer and archaeologist famously known as ‘Lawrence of Arabia’. During World War I, he played a pivotal role as a liaison between British forces and Arab tribal leaders. His deep understanding of Arab culture and fluency in Arabic enabled him to earn the trust of local tribes and form a close alliance with Emir Faisal (1885-1933), a key figure in the Great Arab Revolt. Operating under harsh desert conditions, Lawrence helped orchestrate daring guerrilla raids that significantly disrupted Ottoman infrastructure, notably targeting the Hejaz Railway, a vital supply line. Many of these operations passed through or originated from Wadi Rum, underscoring its strategic importance. Lawrence was captivated by the stark beauty and haunting solitude of the desert, immortalizing its towering cliffs and shifting sands in his acclaimed memoir, ‘Seven Pillars of Wisdom’:

“We looked up on the left to a long wall of rock, sheering in like a thousand foot wave towards the middle of the valley; whose other arc, to the right, was an opposing line of steep, red broken hills. We rode up the slope, crashing our way through the brittle undergrowth… The hills on the right grew taller and sharper, a fair counterpart of the other side which straightened itself to one massive rampart of redness. They drew together until only two miles divided them: and then, towering gradually till their parallel parapets must have been a thousand feet above us, ran forward in an avenue for miles… The crags were capped in nests of domes, less hotly red than the body of the hill; rather grey and shallow. They gave the finishing semblance of Byzantine architecture to this irresistible place: this processional way greater than imagination.”

Thomas Edward Lawrence: Seven Pillars of Wisdom (1926)

Today, Wadi Rum is a UNESCO World Heritage Site (designated in 2011), recognized for both its natural splendor and cultural legacy. The desert remains home to semi-nomadic Bedouin tribes who continue to uphold centuries-old traditions of desert life. Their intimate connection to the land has been crucial in transforming Wadi Rum into a sustainable destination for eco-tourism and adventure travel. Visitors can explore this extraordinary terrain through guided jeep tours, camel treks, and overnight stays in Bedouin-style camps – many equipped with modern amenities while preserving traditional aesthetics. For a more futuristic experience, some may opt for Martian-style bubble tents, offering panoramic desert views beneath a canopy of stars. For outdoor enthusiasts, Wadi Rum offers hundreds of hiking and climbing routes suitable for all levels of experience, from gentle trails winding through narrow gorges to technical ascents up sheer rock faces. Among the most popular challenges are the summit of Jebel Umm Ishrin, one of the region’s highest peaks, and the iconic Jebel Burdah rock bridge, a natural stone arch perched dramatically above the desert floor. With minimal light pollution and clear skies, Wadi Rum is also renowned as one of the world’s premier stargazing destinations, where the Milky Way stretches across the sky in breathtaking clarity.

Day 9 – Aqaba

The only coastal city in Jordan, Aqaba, situated at the crossroads of three countries – Egypt, Israel, and Jordan – holds immense historical and strategic significance as both a vital commercial hub and a gateway between continents. Its freshwater springs and its location at the northeastern tip of the Red Sea – where Asia meets Africa – have made it an essential port for millennia.

In ancient times, Aqaba served as a key stopover along trade routes connecting the Arabian interior with the Mediterranean world. During the Islamic period, it became a staging point for pilgrims en route to Mecca. In modern history, Aqaba is best remembered for the pivotal Battel of Aqaba in 1917, during the First World War. Arab forces, guided strategically by British officer Lawrence of Arabia, launched a daring overland assault on the city from the desert, surprising the entrenched Ottoman defenders, who had fortified Aqaba only from the sea. The successful capture of the port enabled the British to funnel supplies to the Arab Revolt, dramatically shifting the balance in the campaign against the Ottoman Empire in the region.

Aqaba’s long and storied past offers visitors numerous archaeological and historical sites to explore. Among the most significant is the ancient fortified Islamic town of Ayla, established in the 7th century as one of the earliest Islamic settlements outside the Arabian Peninsula. Its remains include sections of defensive walls, city gates, and street layouts, offering a glimpse into the town’s once-thriving commercial and religious life. Another prominent landmark is the Mamluk Fort, originally constructed in the 16th century and later renovated by the Ottomans. This coastal fortress played a strategic role in protecting Red Sea trade routes and now stands as a testament to Aqaba’s military heritage. Located nearby, the Aqaba Archaeological Museum provides deeper context for these ruins, housing artifacts recovered from Ayla and other regional excavations. Its exhibits trace the city’s evolution from a Bronze Age settlement to a significant Islamic and Ottoman stronghold.

Beyond its historical treasures, Aqaba is equally renowned for its natural beauty – particularly beneath the surface of the Red Sea. South of the city, away from the bustle of the commercial port, the coastline opens to an underwater paradise. The crystal-clear waters are home to vibrant coral reefs teeming with marine life, including colorful fish, sea turtles, and occasional dolphins. With visibility often exceeding 30 meters, the area is considered one of the world’s premier destinations for scuba diving and snorkeling. Popular dive sites such as the Japanese Garden, Rainbow Reef, the Cedar Pride wreck, and Power Station attract divers of all levels, offering a mesmerizing glimpse into the Red Sea’s rich aquatic ecosystem.

Sources

https://international.visitjordan.com/

https://visitpetra.jo/en

https://www.wadirumnomads.com