From the depths of a valley, at the end of a narrow canyon, lies one of history’s most astonishing achievements: the ancient city of Petra.

Petra is one of the world’s most awe-inspiring and atmospheric archaeological sites – the most iconic legacy of the ancient Nabataean civilization. In just two centuries, the Nabataeans transformed a barren wilderness into a vibrant and thriving metropolis. The tombs and temples carved into the dramatic sandstone cliffs remain enduring testaments to their architectural mastery, spiritual depth, and lasting imprint on the rugged desert landscape.

The Nabataeans, an ancient Arab people, began building Petra around the 4th century BC. Their decision to settle in such an arid, mountainous terrain demonstrated remarkable strategic foresight. Petra was located at the crossroads of major caravan routes that transported frankincense, myrrh, turquoise, peridot, and other gemstones from Arabia, as well as spices, silk, and luxury goods from East Asia to the Mediterranean world. This made Petra the ideal commercial hub for controlling and taxing the region’s vibrant trade network. Yet Petra’s geography offered more than just economic advantage. Spread across a vast plane measuring approximately 23 by 11 kilometers, the city was naturally fortified by steep cliffs. On these rocky outcrops, the Nabataeans built watchtowers to monitor the surrounding region and defend it from raiders or potential invasions by neighboring kingdoms. Access to the city was limited to a single, narrow entrance: the Siq – a 1.2-kilometer-long gorge carved over millennia by erosion. In a desert where water was scarce, Petra held another crucial advantage: it lay at the confluence of several seasonal riverbeds, known as wadis. These natural channels, which funneled flash floodwaters, provided essential water sources for a city of Petra’s scale. Still, choosing such an arid site for their capital posed serious challenges. Yet the Nabataeans not only survived – they thrived, thanks to their extraordinary ingenuity and a sophisticated hydrological system.

Inevitably, Petra’s wealth and strategic location attracted the attention of the Roman Empire. Concerned by the rising power of the Nabataean Kingdom, Emperor Trajan (reign: 98–117 AD) annexed the territory in 106 AD, coinciding with the death of the last Nabataean king, Rabbel II. Although the Nabataeans ceased to exist as a political entity, Petra continued to flourish under Roman rule for several generations. During this period, Roman architectural elements – such as colonnaded streets, temples, and public buildings – were added, blending seamlessly with the city’s existing Nabataean character. However, Petra’s prosperity began to wane as maritime trade routes gradually replaced overland caravans. This economic shift, combined with two devastating earthquakes in the 4th and 8th centuries AD, led to the city’s decline. By the early Islamic period, Petra had largely faded from historical records and was known only to local Bedouins. The city remained hidden from the outside world until 1812, when Johann Ludwig Burckhardt – a Swiss traveler, geographer, and orientalist – rediscovered the site. While traveling through Arabia, Burckhardt assumed the identity of a Muslim scholar, Sheikh Ibrahim Ibn Abdallah, to gain access to the region. His rediscovery not only rekindled global interest in Petra but also marked the beginning of modern archaeological exploration in the area. (Burckhardt would later identify another iconic example of ancient rock-cut architecture: Abu Simbel in Egypt.)

Today, Petra is one of the most visited archaeological sites in the world – an essential stop on any ultimate Jordanian road trip. Designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1985, it is also a protected archaeological park and one of the New Seven Wonders of the World, attracting visitors from across the globe to its windswept valleys, crimson cliffs, and timeless monuments. Despite its global fame, undeniable grandeur, and decades of archaeological exploration, Petra remains a city of secrets. Its vast expanses and silent cliffs still guard untold stories, with much of its ancient fabric buried beneath layers of sand, rubble, and time – awaiting discovery. As archaeological work continues, newly uncovered structures, artifacts, and insights are shedding light on the Nabataeans’ complex society, far-reaching trade networks, and spiritual life – offering revelations that may yet reshape our understanding of this ancient civilization.

While Petra’s most iconic landmarks – such as the Siq, Al-Khazneh [the Treasury], and the Royal Tombs – can be visited on a half-day tour, those who choose to linger are rewarded with a much deeper and more intimate experience. A full day allows for a comprehensive journey along Petra’s main trail, stretching from the Visitor Center to the sacred precinct of Qasr al-Bint [Palace of the Pharaoh’s Daughter], with ample time to explore the Royal Tombs and climb to either Ad-Deir [the Monastery] or the High Place of Sacrifice. With two or more days, the experience becomes truly immersive. Visitors can tackle both major hikes at a more relaxed pace, uncover lesser-known trails, and venture off the beaten path to discover hidden tombs, unexcavated ruins, and panoramic views rarely seen by day-trippers. An extended stay also provides the opportunity to visit nearby Siq al-Barid, commonly known as Little Petra – a smaller, more intimate Nabataean site that likely served as a caravanserai, offering lodging and provisions to traders traveling along the incense and spice routes. Not to be missed is Petra by Night, a rare and evocative way to experience the ancient Nabataean capital as it may have appeared to travelers centuries ago – bathed in candlelight beneath the quiet stillness of the desert night.

| Distance (km) | Ascent (m) | Duration (hour) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main trail: Entrance – Qasr el- Bint | 8 (out-and-back) | 310 | 3.5 – 4 |

| Ad-Deir Hiking Trail | 3.2 (out-and-back) | 211 | 1 – 2 |

| High Place of Sacrifice Hiking Trail | 3.2 (point-to-point) | 170 | 1 – 2 |

Access to Petra begins with a 1.5-kilometer approach through a winding valley that gradually reveals the grandeur of the ancient city. The journey starts at Bab el-Siq [Gateway to the Siq], a broad gorge that already offers intriguing glimpses into Nabataeans ingenuity and spiritual traditions. The first notable features visitors encounter are the Djinn Blocks – cuboid, carved stone monuments whose precise function remains uncertain. According to Arab folklore, these enigmatic structures were believed to be dwellings for djinn [spirits], lending an air of mysticism to the site. Further along the path, two intricately carved tombs come into view, one stacked above the other on the cliffside. Although they seem to form a single complex, they are actually separate structures. The upper tomb – likely the earlier of the two – is the Obelisk Tomb, distinguished by four pyramidal obelisks and a central niche, reflecting Egyptian architectural influence. Directly beneath it lies the Bab el-Siq Triclinium, a rock-cut chamber believed to have been used for funerary banquets, showcasing the refined proportions and decorative elements of the Nabataean Classical style.

Continuing onward, visitors arrive at the Siq – a deep, narrow gorge that serves as a dramatic gateway to the ‘Pink City’. This geological fault, formed by a natural split in the mountain and later shaped by centuries of water flow from the Wadi Musa, offers one of the most breathtaking entrances in the ancient world. The threshold of the Siq is marked by the remains of a once-imposing triumphal arch, a subtle preview of the grandeur that awaits. As the gorge narrows, it reveals a wealth of archaeological and architectural features. Water channels carved into the rock walls, along with remnants of clay pipes embedded in the stone, showcase the Nabataeans’ advanced water management systems. Along the path, visitors encounter reconstructed dams that once controlled flash floods, weathered niches that may have held religious statues or votive offerings, and fragments of the original flagstone paving that lined the ancient route. Mysterious staircases, hewn into the cliff, ascend toward unknown destinations. Among the most evocative carvings is a relief of a man leading two camels – a poignant reminder of the caravans that once passed through these narrow corridors. The interplay of shadow and light, combined with the soaring sandstone walls streaked in hues of rose, gold, and ochre, evokes a sense of growing anticipation. Each twist in the Siq feels like a step back in time, drawing visitors ever closer to the hidden heart of this ancient city.

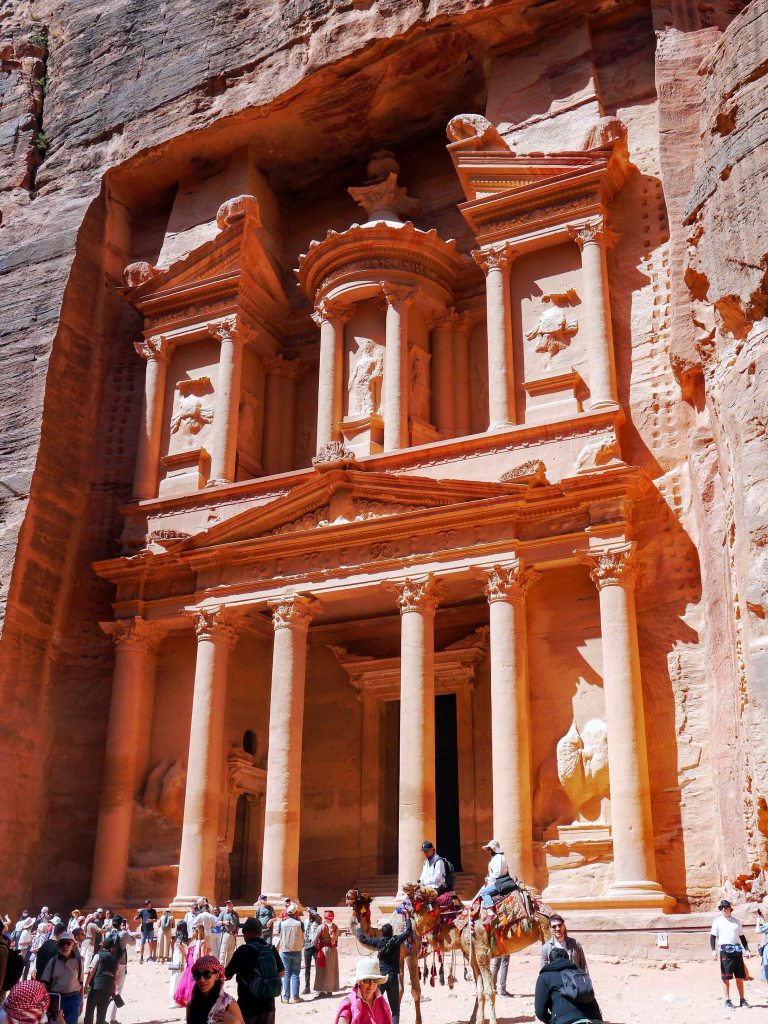

As the Siq descends, it narrows dramatically until, at its deepest and darkest point, the passage suddenly opens to reveal the most iconic of all Petra’s monuments: Al-Khazneh [the Treasury]. The moment is nothing short of theatrical. Through the narrow slit of the gorge, the first glimpse of Al-Khazneh’s pink-hued, meticulously carved façade bursts into view like a vision from another world. This sudden transition – from shadowy confinement to open grandeur, from natural rock to intricate artistry – creates one of the most unforgettable reveals in all of archaeology. Many scholars believe Al-Khazneh likely served as a royal tomb – possibly for Aretas IV, the greatest of the Nabataean kings – though no definitive evidence confirms this. Its popular name stems from Bedouin legend: Khazneh el-Faroun [Treasury of the Pharaoh] According to local folklore, the monument was the magical creation of a powerful wizard who hid his treasure in the urn, over 3.5 meters tall, crowning the façade. Over the centuries, Bedouins fired bullets at the urn, hoping to release the hidden wealth; the bullet marks still visible today are a testament to this enduring belief. Built in the 1st century AD, Al-Khazneh’s lavish façade is a masterpiece of classical influence, blending Nabataean craftsmanship with Hellenistic and Egyptian architectural influences. Rising over 40 meters high, its two-tiered design features soaring Corinthian columns with intricate capitals, an ornate tholos, and sculpted friezes, eagles, and mythological figures – such as Castor and Pollux, the twin protectors of travelers – suggesting both religious significance and cross-cultural inspiration. Yet for all its exterior splendor, the interior of Al-Khazneh is remarkably austere. Behind the elaborate façade lies a large central chamber flanked by three plain, roughly hewn rooms. The walls are unadorned, lacking reliefs or inscriptions that might offer clues to the monument’s original function – deepening its aura of mystery and sacred purpose. What is certain, however, is that the scale and ornamentation of Al-Khazneh far surpass those of most other monuments in Petra, suggesting it held exceptional significance – weather royal, religious, or ceremonial.

Al-Khazneh Trail is a short but rewarding climb to a dramatic overlook above Al-Khazneh, offering a breathtaking and unusual perspective of the monument below. From this lofty perch, the full majesty of the façade is revealed – framed by rugged cliffs and bathed in golden light – an awe-inspiring reminder of Petra’s fusion of natural wonder and human ingenuity. Not to be missed is Petra by Night – an evocative and atmospheric way to experience the ancient Nabataean capital. Held on select evenings, the event begins after sunset – once the site has emptied of daytime visitors – as a candlelit path guides participants through the shadowed Siq, echoing the footsteps of ancient caravans that once passed through this narrow gorge. The journey culminates at the foot of Al-Khazneh, where hundreds of lanterns illuminate the Treasury’s intricate façade in a warm, flickering glow. Accompanied by traditional Bedouin music and storytelling, the evening offers a haunting glimpse into Petra’s past – a rare opportunity to witness the rose-red city beneath the quiet stillness of the desert night, just as it might have appeared centuries ago.

From Al-Khazneh, the path continues into the Outer Siq, also known as the Street of Façades – a dramatic corridor flanked by dozens of monumental tombs carved directly into the sandstone cliffs. These tombs, which vary widely in size and decoration, are arranged across up to four vertical tiers and reflect a broad spectrum of artistic influences and historical periods. Many are partially buried beneath centuries of accumulated sediment, their lower sections obscured by time while their upper façades remain exposed to the elements. Some scholars believe these tightly packed structures represent some of the earliest examples of monumental Nabataean architecture, offering valuable insights into the evolution of Petra’s building traditions. Near the end of the Street of Façades, a rock cut stairway – flanked by several enigmatic djinn blocks – marks the start of the High Place of Sacrifice hiking trail. The grandeur of this necropolis culminates at the far end of the Outer Siq with the classical Theatre. Carved into the mountainside by the Nabataeans in the early 1st century AD, the Theatre is a striking testament to their engineering prowess and openness to foreign cultural influences. Although later modified by the Romans, its original design predates Petra’s annexation and illustrates the Nabataeans’ integration of Greco-Roman urban features while retaining their distinct identity. With seating for up to 7,000 spectators, the Theatre would have hosted public gatherings, ceremonies, and performances – reinforcing Petra’s role not only as a commercial center, but also as a vibrant civic hub of the ancient world.

A short detour to the right, where the Outer Siq opens onto Petra’s central plain, leads to the Royal Tombs – a dramatic row of monumental façades carved into the towering cliffs at the base of Jebel al-Khubtha. Viewed from a distance, these structures create a breathtaking panorama, their grand scale and intricate details silhouetted against the sheer rock face. Believed to have been built for high-ranking individuals – possibly members of Petra’s royal family – these tombs represent some of the most architecturally ambitious and artistically refined monuments in the city. In the absence of inscriptions identifying their original occupants, the tombs have been named based on distinctive architectural features or visual characteristics. The most prominent among them are the Urn Tomb, the Silk Tomb, the Corinthian Tomb, and the Palace Tomb.

The Urn Tomb, named for the large urn that sits atop its pediment, is distinguished by a grand forecourt and two tiers of supporting arches that form an expansive terrace in front of the façade. These features have inspired local legends: according to Bedouin folklore, the arches were believed to conceal sinister dungeons beneath what was once a court of law. Next in line, the Silk Tomb – though smaller in scale – is among the most visually striking due to the vibrant natural banding in its sandstone. Striations of yellow, red, and blue ripple across its surface, creating a tapestry of color that becomes especially radiant in the golden light of the late afternoon sun. The Corinthian Tomb is notable for its richly ornamented yet asymmetrical façade – an uncommon feature in Nabataean architecture, which typically favored balance and harmony. Its elements, including Corinthian capitals, a tholos, and decorative pediments, reflect a strong Hellenistic influence. The sequence concludes with the Palace Tomb. The largest of the group, it was likely inspired by Emperor Nero’s Domus Aurea [Golden House] in Rome. Its towering five-story façade originally extended beyond the height of the cliff into which it was carved, though the uppermost levels have since collapsed. Despite its ruined state, it remains an imposing example of Nabataean ambition and Roman influence. Together, the Royal Tombs stand as a powerful testament to the wealth, cosmopolitan spirit, and artistic sophistication of Nabataean Petra at its zenith.

Returning to the main trail, visitors arrive at the Heart of Petra – the civic and ceremonial center of the ancient city – nestled within the broad expanse of the central basin. Once teeming with life, this area now consists mostly of scattered ruins. Fragmentary remains of the Roman-style Cardo and monumental structures such as the Royal Palace, the Temple of the Winged Lion, the Great Temple, and the Bathing Complex offer tantalizing glimpses into Petra’s former urban grandeur. Enormous piles of rubble are still strewn across the site, silently holding the potential for future discoveries that may further illuminate Nabataean society, architecture, and religious practices. One of the most impressive surviving structures, the so-called Great Temple, is a monumental complex spanning over 7,500 square meters that dominates the archaeological heart of Petra. Adjacent to the Great Temple, archaeologists uncovered one of Petra’s most remarkable and unexpected finds: a vast Bathing Complex. Requiring thousands of liters of water to function, the complex featured its own garden and a grand basin, supported by a sophisticated network of pipes, hydraulic surfaces, and cisterns. Among the better-preserved remains is the Byzantine basilica, notable for its elaborate 6th-century mosaic floor. These intricate panels – depicting animals, geometric designs, and personification of the seasons – offer rare insight into the artistic sensibilities of late antiquity in the region. During excavations, archaeologist also uncovered a cache of 152 papyrus scrolls, now known as the Petra Papyri. Written in Greek, these documents shed light on daily life in Byzantine-era Petra, revealing a vibrant community that remained active long after the city’s Nabataean zenith. Nearby, the remains of a modest Crusader-era fortress add yet another layer to Petra’s rich historical palimpsest, reflecting the city’s continued strategic significance well into the medieval period. Together, these remnants – spanning the Nabataean, Roman, Byzantine, and Crusader periods – create a layered archaeological landscape that speaks to Petra’s enduring importance and historical complexity across the ages.

Beyond the ruins of the Great Temple and through the imposing triple-arched Temenos Gate lies Petra’s most sacred surviving monument: Qasr el-Bint [Palace of the Pharaoh’s Daughter]. Despite its name, this massive structure is not a palace but a temple – possibly dedicated to Dhu-Shara, the chief deity of the Nabataean pantheon. While Petra’s strategic location offered numerous advantages, its position at the junction of the Arabian Plate and the Sinai Subplate made the region highly prone to seismic activity. Throughout its history, Petra endured several powerful earthquakes, many of which caused the collapse of its freestanding structures. Remarkably, Qasr el-Bint is the only major freestanding Nabataean building in Petra to have survived. The temple’s square layout and the seismic-dampening wooden beams integrated into the stone masonry helped mitigate earthquake damage, making it one of the earliest known examples of earthquake-resistant architecture. Although much of its decoration has been lost to time and seismic damage, traces of stucco and marble veneer offer a faint but evocative glimpse into its former splendor. Just beyond Qasr el-Bint, a path crosses the Wadi Musa and begins an arduous yet deeply rewarding ascent along the Ad-Deir hiking trail.

Additionally, the Petra Museum, located near the main entrance to the archaeological park, serves as an excellent complement to the site itself. Artifacts uncovered throughout the area are displayed in several thematic halls. The exhibits trace Petra’s transformation from a prehistoric settlement into a thriving Nabataean metropolis, and later, a Roman and Byzantine city. The collection includes architectural fragments, intricately carved statues, religious artifacts, pottery, and coins that highlight the city’s importance as a center of trade, craftsmanship, and cultural exchange. The museum also provides insight into the Nabataeans’ sophisticated water management system, which was crucial for sustaining life in the arid desert environment.

Located on the northern outskirts of Petra, Siq al-Barid – commonly known as Little Petra – is a small but historically significant Nabataean site that once served as a caravanserai, providing lodging and provisions to traders and their camels traveling along the incense and spice routes. Unlike the main Petra complex, Little Petra appears to have been primarily residential and commercial, as relatively few tombs have been uncovered in the area. The narrow gorge and surrounding cliffs showcase classic Nabataean rock-cut architecture, including façades, staircases, cisterns, and niches that once held religious offerings. Among the site’s most remarkable features is the Painted House, a rare example of surviving Nabataean interior decoration. Its plastered ceiling and walls are adorned with delicate frescoes depicting interlacing vines, flowers, bunches of grapes, birds, and mythological figures such as Eros with his bow and Pan playing his flute – imagery that reflects strong Hellenistic influence. Though more modest in scale, Little Petra offers a quieter, more intimate glimpse into the everyday life and artistic sophistication of the Nabataeans, away from the crowds of the main Petra site.

Sources

https://international.visitjordan.com/

https://international.visitjordan.com/Wheretogo/Petra

https://visitpetra.jo/en