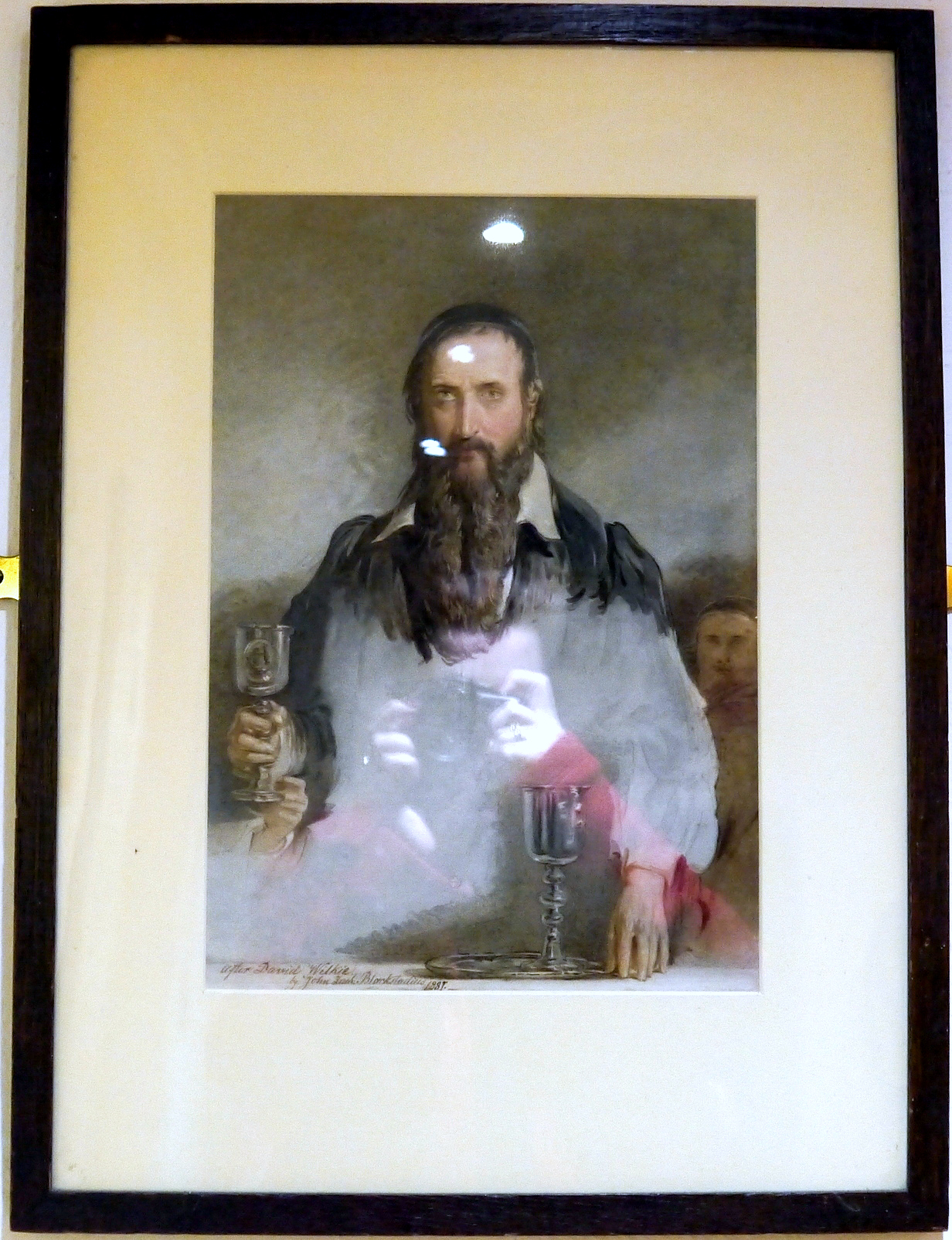

No one in Scottish history has received as much adoration and as much vilification as John Knox.

“John Knox, a Scotsman by nation and a great enemy of the Catholic Church, arrived in the town. This man was so audacious and learned and factious, and so eloquent that he managed men’s souls as he wished.”

(The Ancient Chronicles of Dieppe)

During the Middle Ages, religious beliefs played a crucial role in shaping individuals’ identities and their perceptions of the world. However, as the 16th century unfolded, Europe experienced profound and swift transformations. Established beliefs came under scrutiny due to emerging religious ideologies. This ongoing debate eventually escalated into a fierce conflict that divided Europe between Catholic adherents and proponents of Protestants reforms. The two most important European reformers who broke away from the Catholic Church were Martin Luther (1483-1546), a German theologian, and Jean Calvin (1509-1564), a French theologian based in Genève.

The leader of the Protestant Reformation in Scotland was John Knox (1513-1572), who was born in Haddington, near Edinburgh. He pursued his studies at St Andrews University and was ordained as a priest in 1536. Over time, Knox grew increasingly convinced of the necessity for religious reform. In 1547, he participated in the Protestant occupation of St Andrews Castle, which led to his punishment of serving as a galley slave in the French navy for a duration of two years.

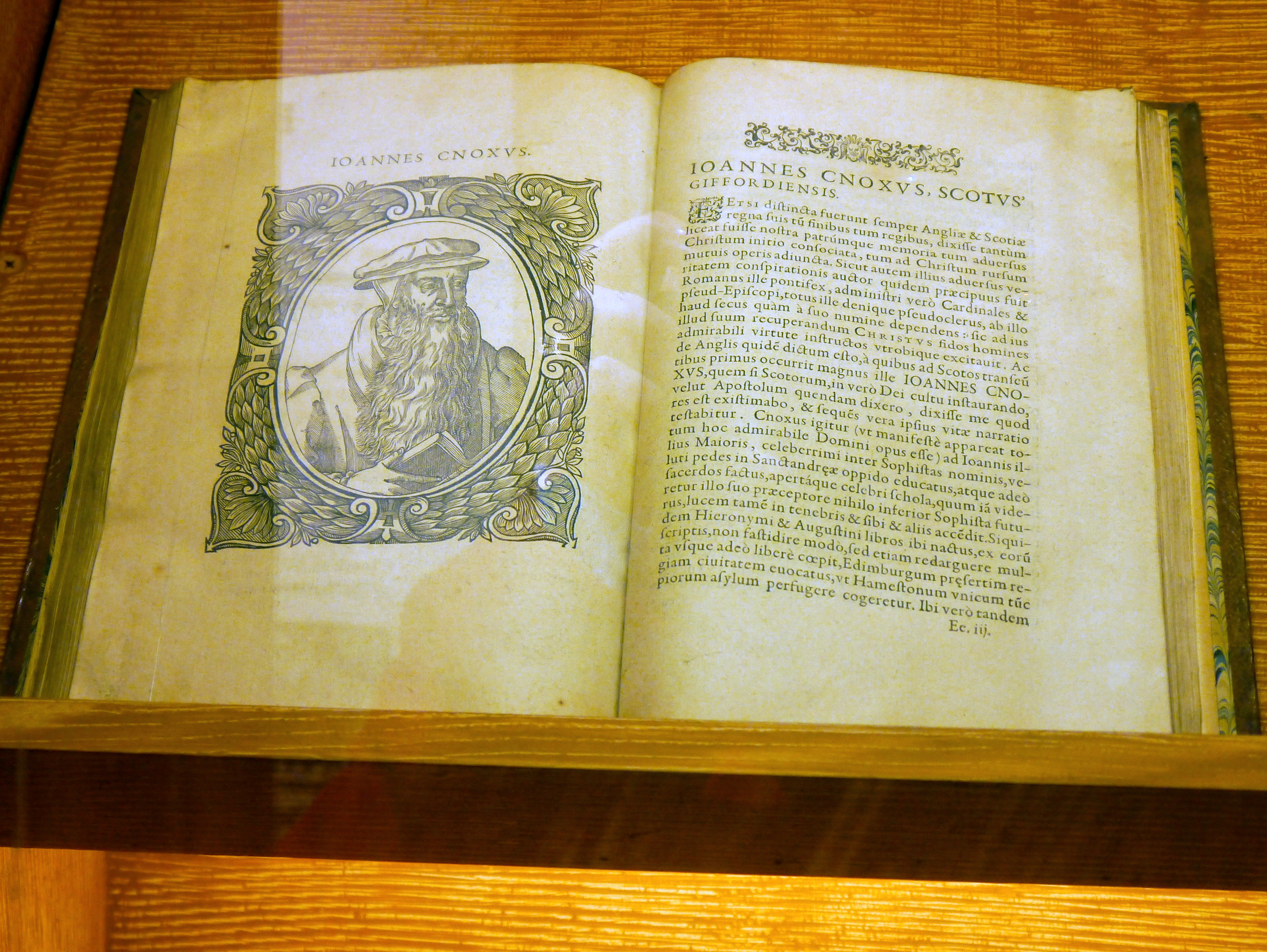

After being released from captivity, Knox embarked on extensive travels throughout England and Europe, immersing himself in the study of new religious ideas and engaging with influential reformers. In 1550, following the ascension of Mary Tudor (reign: 1553-1558), a Catholic ruler, to the English throne, John Knox played a significant role in the English Reformation while also expressing his belief that female rule was unnatural. Settling in Genève in 1553, he further developed his theological perspectives under the influence of Calvin. Knox considered himself fortunate to be part of the Reformed Protestant community in Genève, describing it as “the most perfect school of Christ that ever was on earth since the days of the apostles”. During his time there, he also served as a pastor for the English-speaking congregation. Members of his congregation undertook the translation of the Bible into English, which served as the foundation for the first Scottish edition of the English Bible known as the ‘Geneva Bible’ printed in 1579. Overall, the widespread availability of printed books played a pivotal role in disseminating the reformers’ new ideas.

In 1559, John Knox accepted the invitation of Protestant nobles and returned to Scotland. At the time, Scotland was under the rule of Queen Regent Marie de Guise (regency: 1554-1560), who was the widow of Scottish King James V (reign: 1513-1542) and the mother of Mary Queen of Scots. Edinburgh was witnessing a period of increasing prosperity, with affluent merchants and craftsmen forming guilds to protect their economic monopolies and civic privileges. In exchange for their support, the Catholic Church bestowed legitimacy upon their authority and wealth. However, the death of Marie de Guise in 1560 threw Scottish society into turmoil. Taking advantage of the situation, Knox was able to rally the Protestant forces in Scotland. As a Minister of St Giles’ Cathedral in Edinburgh, which was arguably the most influential church in the country, he delivered passionate and outspoken sermons denouncing the Catholic Church and challenging the authority of the Crown. He found support from the Lords of the Congregation, a group of Scottish nobles who had pledged to oppose the influence of Catholicism. Their violent struggle for control over the nation and its religious direction pushed Scotland to the brink of civil war.

Although the early Scottish Protestants initially aligned with Lutheranism, the Reformation of 1560 took on a strong Calvinist character. This was partially influenced by John Knox’s connection with Calvin and the resonance of Calvin’s more radical ideas with Scotland. As a result, in 1560, the Scottish Parliament rejected the authority of the Pope over the Scottish Church, establishing Protestantism as the national religion. The Protestant ‘Scots Confession’ was adopted as the official statement of belief, prioritizing the authority of the Bible over that of the Church.

In the ‘First Book of Discipline’, John Knox and his colleagues outlined their vision for a righteous society. They advocated that “Christ’s evangel be truly and openly preached in every Kirk and Assembly of this Realm, and that all doctrine repugnant to the same be utterly suppressed as damnable to man’s salvation”. The Protestant Reformers had ambitious plans for education, aiming to make it compulsory for both the wealthy and the less privileged to educate their children. They also envisioned the new Church as a central pillar of a well-ordered society, where offenders would publicly repent in church and persistent or serious offenders would face excommunication. Moreover, they proposed a support system for those unable to work or care for themselves but held negative views towards vagrancy and begging, which were prevalent issues in Scotland at the time.

John Knox vehemently opposed the resurgence of Catholicism and feared the return of Mary Queen of Scots (reign: 1542-1567), who, as the only surviving legitimate child of King James V, inherited the throne at the age of six days upon her father’s death. At the time, she was the Queen Consort of France. After the death of her husband, King Frances II (reign: 1559-1560), she returned to Scotland in 1561, putting the fate of the Scottish Reformation in a precarious position. Despite publicly acknowledging Protestantism as the national religion, the Queen privately continued to celebrate Mass. By 1567, the atmosphere of instability and political intrigue in the Scottish Court had reached its boiling point. A group of power-hungry nobles coerced the Queen into abdicating in favor of her one-year-old son, James VI (reign: 1567-1625). Fearing for her safety, she fled to England the following year, never to return to Scotland. During her absence, her loyal supporters, known as the ‘Queen’s Men’, campaigned for her restoration to the throne and seized control of the formidable Edinburgh Castle in defiance of the Protestant Government. As the situation escalated into a civil war, Edinburgh became increasingly perilous. In May 1571, John Knox made the decision to leave the city. However, a year later, despite his advanced age (he was almost 60 years old) and failing health, he returned to continue preaching.

John Knox passed away in Edinburgh on 24 November 1572, and his death was mourned by many as a national tragedy. The Earl of Morton, who was the Protestant Regent at the time, described him as a man “who never feared the face of man”. Although John Knox witnessed the establishment of the Protestant religion in Scotland during his lifetime, his vision of a godly society remained unrealized. The nobility who supported the 1560 revolution believed that the Protestant Church should still be under the authority of the monarchy and parliament. They also did not fully endorse Knox’s ‘First Book of Discipline’. While many of Knox’s ideas were embraced, they were not implemented in their entirety, leading to certain historical misunderstandings regarding his beliefs.

“So I end, rendering my troubled and sorrowful spirit in the hands of the Eternal God, earnestly trusting at His good pleasure to be freed from the cares of this miserable life, and to rest with Christ Jesus, my only hope and life.”

(Knox’s prayer at the end of his life)

Sources

https://www.scottishstorytellingcentre.com/john-knox-house