The Hawaiian archipelago is constantly shaped by active geological forces, oceanic currents, abundant rainfall, and lush vegetation. Amidst these natural phenomena, human activities have exerted a significant impact, as the islands have endured successive waves of invasion, immigration, and expropriation. Consequently, the native Hawaiian population, now dwindled to 10.8 percent, has lost its kingdom.

Encompassing less than 2,000 years, much of Hawaiian history remains shrouded in legend. The Polynesians, whose culture emerged in the island clusters of Samoa and Tonga between 2,000 and 1,500 BC, possessed impressive seafaring prowess. They embarked on voyages using twin-hulled canoes capable of carrying up to 100 passengers, along with essential crops for cultivation, including taro, sweet potato, coconut, and banana, as well as pairs of domesticated animals like pigs and chickens. These intrepid explorers successfully colonized Tahiti and the Marquesas Islands by the 1st century AD.

Around 300 AD, the Marquesans embarked on a daring 5,000-kilometer ocean crossing to discover the Hawaiian Islands. The early Hawaiians were adept farmers. They implemented a unique land management system known as ‘ahupuaa’, dividing the land into pie-shaped wedges running from the mountaintop to the sea. This division ensured that each district had access to a wide array of island resources. Additionally, they developed some of the most extensive irrigation systems in Polynesia. These early settlers also established a sophisticated spiritual culture. Hawaiian ancestral chants, meticulously preserved through oral tradition, traced family lineages back to the 1st century. Their life revolved around the extended family unit, comprising 250 to 300 individuals, where every member from child to grandparent played a vital role. Cultural values emphasized a deep connection to the land, cooperation, and hard work.

“After a while he felt nothing, he no longer existed as a singular thing. He and the land and the weeds he pulled and the heart-shaped glistening taro leaves and the mud and the air seemed one. He looked at his hand and no longer felt it, he could no longer name it. His hand flowed into leaf that flowed into earth that poured into the lava heart of his island pouring into sea.”

Kiana Davenport: Song of the Exile (1999)

During the 12th and 13th centuries, new waves of Polynesian settlers from Tahiti arrived in Hawaii, marking a significant chapter in its history. They established a rigid caste-based society wherein they positioned themselves as chiefs, exerting authority over the lives of commoners, enforced through the strict ‘kapu’ system – a code of conduct consisting of laws and regulations. Under this system, the ‘Kahili’ imposed constraints on interactions with chiefs, extending to individuals with spiritual authority. For example, commoners were prohibited from touching the garments or shadows of nobility or elevating their heads higher than theirs. Meanwhile, the ‘Ai kapu’ regulated interactions between genders, forbidding women, for example, from eating with men. Moreover, certain foods like pork, bananas, and coconuts were strictly off-limits for women to consume or even handle. Infractions of these laws incurred swift and fatal punishments. Additionally, the Tahitians constructed heiau [temples], in various architectural styles, ranging from simple earth terraces to elaborate stone platforms, depending on their purpose and location. As the population and chiefdoms grew, four distinct chiefdoms eventually emerged: Hawaii, Maui, Oahu, and Kauai. According to Hawaiian tradition, the Tahitian priest Paao played a key role in these reforms. He introduced certain customs, including the practice of human sacrifice, established a line of high priests, and brought a ‘pure’ chief named Pili, likely from Samoa, to consolidate political power and rule over the Hawaiian Islands.

Although British sea captain and explorer James Cook (1728-1779) is commonly credited with the ‘discovery’ of Hawaii, having landed on Kauai Island in 1778, compelling evidence suggests that Spanish ships preceded him by more than 200 years. During the mid-16th century, Spanish galleons undertook annual voyages across the Pacific between their colonies in Mexico and newly established bases in the Philippines. In 1542, one such fleet stumbled upon the Hawaiian Islands. It seems that the exact route was kept secret to protect the Spanish trade monopoly against rival powers. The timing of Cook’s arrival at Hawaii Island’s Kealakekua Bay in 1779 is a striking historical irony. His ships, the Resolution and Discovery, arrived during the annual ‘makahiki’ festival – an ancient Hawaiian New Year festival honoring Lono, the god of fertility, agriculture, rainfall, music, and peace. The appearance of the British vessels closely resembled Hawaiian prophecies predicting the return of Lono on a floating island. To Cook’s surprise, the Hawaiians greeted him with reverence surpassing anything he had experienced in the Pacific. However, tensions arose upon his departure. By this time, the Hawaiians had begun to doubt the divinity of the haole [white, foreigner], and escalating squabbles culminated in a violent confrontation, resulting in Cook being fatally stabbed. After Cook’s visit and the publication of several books recounting his voyages, other explorers arrived.

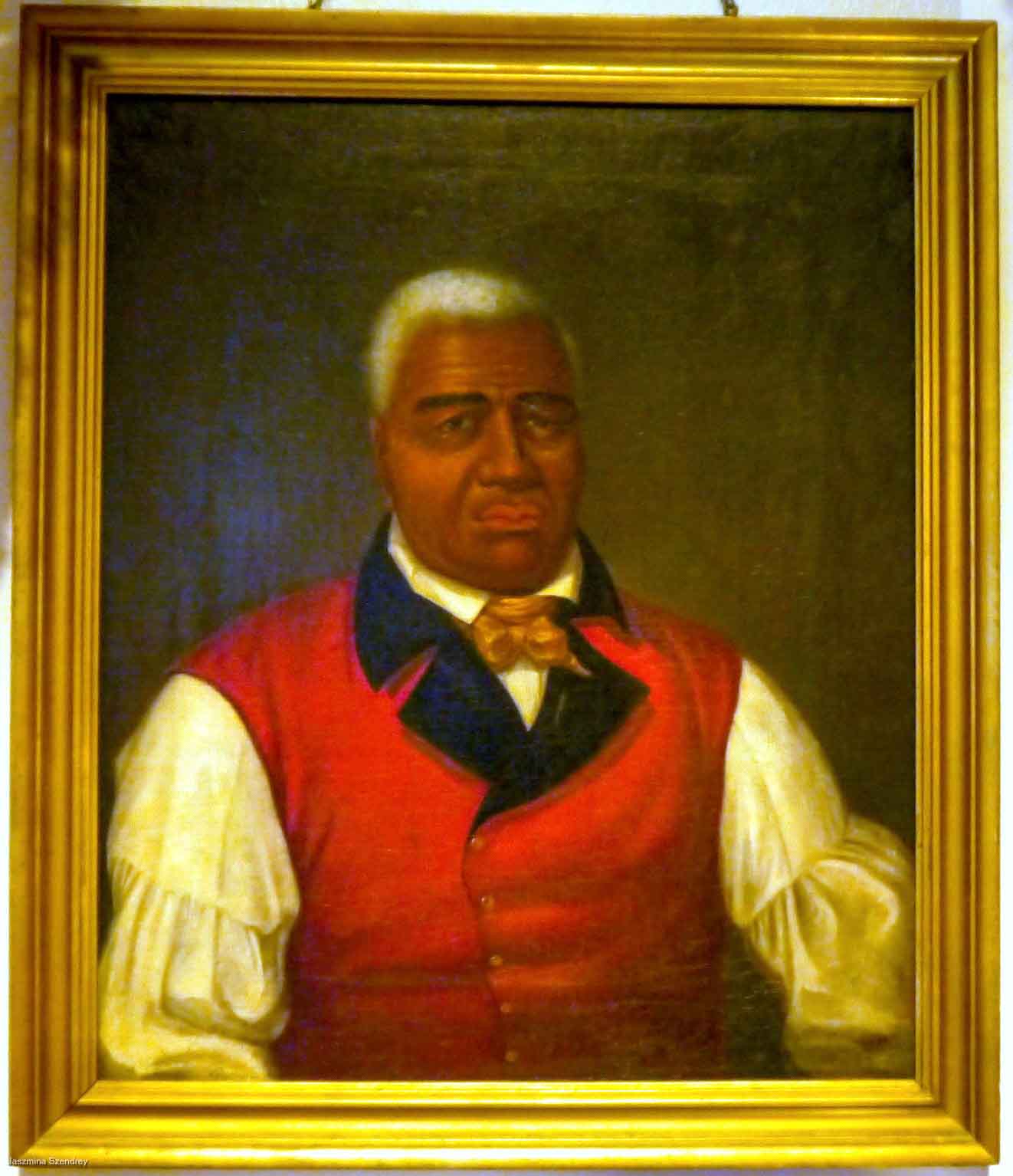

During the 18th century, chiefs frequently found themselves embroiled in power struggles. Kamehameha the Great (reign: 1795-1819), an ambitious chief from Kohala on Hawaii Island, embarked on a mission to unify the islands. He was renowned for his prowess in battle and strategic acumen. When faced with obstacles in achieving his goals, a revered kahuna [prophet, priest] named Kapoukahi suggested constructing a luakini heiau [sacrificial temple] to appease the war god Kūkailimoku and offer his key rivals as sacrifices. Employing a mix of coercion and incentives, he compelled the chiefs to surrender, ultimately uniting the chiefdoms into a single kingdom in 1810, which he ruled until his death in 1819.

When the old conqueror passed away, he left a leadership void that his 22-year-old son King Kamehameha II (reign: 1819-1824) was unable to fill. In 1820, the first American Protestant missionaries arrived in Hawaii, with many more to follow in the subsequent decades. They baptized many Hawaiians, asserting that the main purpose of their work was to ‘purify’ the locals. The King never converted to Christianity because he refused to relinquish four of his five wives and his fondness for alcohol. Regarding the population, instead of entirely abandoning traditional beliefs, most native Hawaiians merged their Indigenous religion with Christianity. With the support of the king’s mother Keōpūolani, the missionaries leveraged their influence to abolish many traditional practices and persuaded the King to abandon the kapu system. A pivotal moment occurred when the King shared a meal with women – his mother Keōpūolani and his father’s favorite wife, Kaahumanu. This act was seen as a symbolic gesture that invalidated all traditional rules. As a result of this shifting landscape, new laws such as banning gambling, alcohol consumption, hula dancing, and polygamy were implemented under the guidance of the missionaries. During his reign, Kamehameha II had depleted the kingdom’s finances, despite stripping the native forests by selling the expensive Hawaiian sandalwood to China. To develop closer diplomatic ties with King George IV (reign: 1820-1830), he and his wife sailed to England. Instead of meeting the king as they had hoped, they both contracted measles and died of the disease in 1824.

King Kamehameha III (reign: 1825-1854) ascended the throne at the age of 11 following the passing of his brother. However, true power rested in the hands of the formidable regent, Queen Kaahumanu, who orchestrated the peaceful conversion of the entire kingdom to Christianity. In 1840, guided by his haole advisors, the King willingly relinquished his absolute power to establish a constitutional monarchy. This pivotal step delineated the rights of citizens and reorganized the government into executive, legislative, and judicial branches. The informal council of chiefs was supplanted by an American-dominated cabinet, while the chiefs assumed roles in the House of Nobles. Recognizing the imperative of shielding Hawaii from foreign threats, the King dispatched diplomatic missions to the United States and Europe in 1842. This initiative led to the recognition of Hawaiian independence in treaties signed by numerous foreign powers. The King’s ambition was to modernize Hawaii by adopting Western practices while preserving its cultural identity. In 1845, the decision was made to relocate the seat of government from Lahaina to Honolulu, partly motivated by the strategic advantage of its proximity to Pearl Harbor, one of the world’s premier natural harbors.

At the dawn of Kamehameha III’s reign, the native population stood at approximately 150,000, a significant decline from the nearly one million inhabitants at the time of Captain Cook’s arrival in 1778. Regrettably, the once-isolated Hawaiian people, renowned for their strength and health, lacked immunity against Western diseases. Increased contact with whaling and trading ships from around the world had spread diseases such as syphilis, measles, typhoid, and whooping cough, ravaging the population. Throughout his rule, successive epidemics further decimated the population. To bolster the monarchy’s finances and address the commoners’ right to land ownership, the King proclaimed the Great Mahele [land division] in 1848, making millions of acres available for purchase by private individuals. Despite the intention to empower commoners with land ownership, most of the acquired deeds ended up in the hands of Western planters, highlighting a disparity in understanding property ownership. The descendants of missionaries, prioritizing commerce over religion, spearheaded agricultural ventures, particularly in plantation-style cultivation of sugar cane, coffee, and pineapples. These extensive operations required a labor force willing to endure arduous hours, meager wages, and cruel treatment, leading to a decline in native Hawaiian participation due to social upheavals and devastating foreign diseases. Nonetheless, the labor demand was fulfilled by immigrants from China, Japan, Korea, and the Philippines. Over time, these contract laborers assimilated into Hawaiian society, with Japanese immigrants constituting over half of Hawaii’s population by 1900.

“Extermination of each unique culture is another death of human conscience.”

Kiana Davenport: House of Many Gods (2006)

Following Kamehameha III’s death in 1854, a succession of short-lived rulers attempted to address the problem of the rapidly diminishing native population. Upon assuming the throne, King Kamehameha IV (reign: 1855-1863) faced a growing American presence in the Hawaiian Islands, which exerted economic and political pressure on the Kingdom. Sugar producers, in particular, advocated for annexation by the United States to facilitate free trade. However, the King strongly opposed annexation, fearing it would spell the end of the monarchy and the Hawaiian people. Instead, he and his wife Queen Emma focused on reducing Hawaii’s reliance on American trade and improving healthcare and education for their subjects, who were being ravaged by diseases such as leprosy and influenza. King Kamehameha V (reign: 1863-1872) issued a new constitution in 1864 aimed at bolstering the monarchy’s authority and enacted legislation to protect the rights of foreign laborers. He opposed a bill granting foreign merchants the right to sell liquor directly to Native Hawaiians, recognizing alcoholism as a significant contributor to the declining native population, exacerbated by their inability to metabolize alcohol. Additionally, he advocated for the resurgence of traditional customs. Tourism to the islands flourished during his reign, attracting notable visitors like Mark Twain, the famous American writer. His passing marked the conclusion of the direct lineage of kings descended from Kamehameha the Great. William Lunalilo (reign: 1873-1874) was the first king elected by the Hawaiian legislature. He aimed to reverse some of the changes implemented by his predecessor and enhance the democratic nature of the Hawaiian government. Additionally, he sought to address Hawaii’s economic challenges. The kingdom was grappling with an economic downturn, exacerbated by the rapid decline of the whaling industry. However, his reign was short-lived, lasting only a year, as he struggled with alcoholism and tuberculosis.

In 1874, a heated election for the throne unfolded within the legislature, with contenders David Kalākaua and Emma, Queen Consort of Kamehameha IV, in fierce competition. Unrest broke out, prompting the deployment of troops from the United States and Britain to restore order. Ultimately, David Kalākaua (reign: 1874-1891) ascended to the throne. In his first year of reign, the King negotiated the Reciprocity Treaty between the United States of America and the Hawaiian Kingdom. This treaty granted unrestricted access to the American market for sugar and other native products. In exchange, the U.S. received assurances that Hawaii would refrain from selling or leasing its lands to other foreign powers. This agreement spurred considerable American investment in sugarcane plantations across Hawaii. Subsequently, an extension of the treaty granted the United States exclusive use of Pearl Harbor. King Kalākaua led a cultural renaissance by promoting the revival of Hawaii’s sacred customs and traditions. He passed legislation allowing Hawaiian kahuna [prophet, priest] to publicly practice chanting and herbal healing. Additionally, he encouraged Hawaiians to broaden their educational pursuits beyond their native land. In 1881, Kalākaua made history by becoming the first monarch to circumnavigate the globe. In 1882, the construction of Iolani Palace, the official residence of the Hawaiian monarchs, was completed. The palace was remarkably advanced for its time, equipped with the latest amenities such as the first electric lights in Hawaii, indoor plumbing, and even a telephone, predating similar features in the White House and Buckingham Palace.

King Kalākaua’s vision of a Polynesian confederation, with Hawaii as its capital, aligned with the agenda of annexationists seeking the takeover of Hawaii by the United States. Honolulu’s haole elite launched a campaign against the king, highlighting his flagrant abuse of royal privileges: misuse of public funds, bribery, fraud, vote-buying, dismissal of dissenting white cabinet members and ministers, and extravagant spending. They also criticized his indulgences, such as lavish parties, alcohol consumption, participation in hula dancing, leniency towards opium use, and frequent pleasure trips. In 1887, the Honolulu Rifles, two hundred armed soldiers in the king’s service, switched allegiance to the Hawaiian League, a coalition of influential white merchants conspiring to diminish the king’s authority. Consequently, King Kalākaua was compelled to sign the Bayonet Constitution, which significantly reduced the power of the Hawaiian monarchy while bolstering the legislature and the government’s cabinet. By the time of Kalakaua’s death in 1891, many had likely forgotten his status as Hawaii’s Renaissance Man due to his political shortcomings. He perceived his islands and people as fragile, facing the threat of total extinction. Nevertheless, he briefly rekindled a sense of pride in their history and culture. In 1891, while traveling to San Francisco, King Kalākaua died under mysterious circumstances, with some Hawaiians believing he was poisoned.

King Kalākaua was succeeded by his sister Queen Liliuokalani (reign: 1891-1893), who faced numerous challenges. Haole sugar tycoons campaigned for Hawaii’s annexation by the U.S., while Native Hawaiian groups vehemently opposed annexation, leading to widespread unrest. Additionally, ethnic groups imported for ‘slave work’ on plantations organized strikes demanding decent wages and humane working conditions. The constant threat of rebellion disrupted international trade, plunging the islands into chaos. In 1893, the Queen attempted to introduce a new constitution that would restrict voting rights to true Hawaiians and eliminate wealth qualifications for running for office or casting ballots. She aimed to become an absolute monarch, no longer requiring cabinet sanction, and ministers would serve at her discretion. Furthermore, she pledged to eradicate all talk of annexation. However, before she could legalize her constitution, the ‘Committee of Safety’, comprised mostly of Euro-American sugar and pineapple-growing businessmen, overthrew Queen Liliuokalani with assistance from the American minister to Hawaii and illegally requisitioned troops of U.S. soldiers and marines. The military seized government buildings and paraded light cannons through the streets, while the warship USS Boston aimed its guns at Iolani Palace. The committee members formed a Provisional Government and declared martial law. The Queen surrendered under protest and appealed to the United States government for justice. U.S. President Grover Cleveland (in office: 1893-1897) investigated the matter and demanded the queen’s restoration. However, the Provisional Government refused and established itself as the Republic of Hawaii in 1894, with the clear intention of seeking annexation by the United States. Although Cleveland refused to annex the pirated kingdom, his successor, William McKinley (in office: 1897-1901), signed into law the resolution to annex the Hawaiian Islands in 1898. The underlying goal was to use Pearl Harbor as a naval base to fight the Spanish in Guam and the Philippines during the Spanish-American War.

Pearl Harbor remains a poignant symbol in American history. It was on December 7, 1941, when the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service launched a surprise military strike against the American naval base there. Alternative views suggest that President Franklin D. Roosevelt (in office: 1933-1945), constrained by the American public’s opposition to direct U.S. involvement in the fight against Nazi Germany, intentionally stationed the fleet in Pearl Harbor to provoke a Japanese attack, thus leading to the United States joining the war alongside Britain. During the attack, in just over an hour, Japanese bombers inflicted severe damage on U.S. military installations: six ships were sunk, thirteen ships were damaged, 188 aircraft were destroyed, with an additional 159 aircraft damaged, and 2,403 people were killed. Japanese losses, in comparison, were relatively light. Within 24 hours, Hawaii’s government was replaced by a military one that remained in power throughout World War II. More than 2,000 Japanese-American residents of Hawaii were rounded up and sent to internment camps. After the war, there was a shift in political power away from the plantation owners. Strikes, though violent, dealt the initial blow, effectively shutting down the plantations for 79 days. At the same time, Hawaii’s underprivileged class began leveraging the power of the ballot, propelling the descendants of immigrant laborers, who were born in Hawaii and were U.S. citizens, into political positions. Eventually, in 1959, the US Congress proposed making Hawaii the 50th state of the union, and following a referendum in Hawaii 94.3% of the voters approved the proposition.

Militarism, alongside colonialism, has significantly shaped the cultural and political landscape of Hawaii. Since the U.S. military played a crucial role in the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii in 1893, the islands have become a focal point of U.S. military strategy in the Pacific region. The primary conflict between indigenous Hawaiians and the military revolves around the control and use of land. Hawaii stands out as one of the most densely militarized regions under U.S. control. In the 1970s, Hawaiians began organizing movements to reclaim certain lands that had served as military target practice areas for decades. An ongoing example of this struggle for demilitarization is Mākua Valley on Oahu. Natives consider this area sacred, their Mother Earth, as ‘mākua’ means parents in the Hawaiian language, indicating its genealogical significance. The valley was once a pristine land, encompassing thousands of acres teeming with flora and fauna, where native Hawaiians worshipped at heiau [temples] and preserved the bones of their ancestors in caves. However, during World War II, hundreds of residents were evicted, and their homes and churches were used for target practice. In the ensuing decades, military exercises have included ship-to-shore and aerial bombardment, amphibious assault, mortar, napalm, and rocket training, as well as ammunition disposal. Today, the area resembles a cratered moonscape devoid of life, dotted with unexploded ordnances. Toxic chemicals and radioactive fallout from explosives have contaminated the soil and groundwater, leading to respiratory diseases, cancer, and leukemia among locals.

The advent of air travel has arguably had a more profound impact on Hawaii than any other imported technology. Not only did it establish Oahu as the center of U.S. military defense in the Pacific, but it also paved the way for mass tourism. While the plantations once drove the economy, many of the once-thriving sugar and pineapple fields now lie fallow. Hawaii’s fortunes have since become closely intertwined with the fluctuations of tourism and real estate prices. Despite the passage of time, certain Native Hawaiian groups continue to dispute the annexation, asserting that Hawaii remains an independent kingdom. Moreover, there has been a resurgence of interest in native culture, language, and crafts among the locals. As of 2020, the Hawaiian Islands are home to over 1.5 million people, with Native Hawaiians comprising 10.8 percent of the population.

“Inside the terminal at Keahole, they sat waiting to board, watching husky Hawaiians load luggage onto baggage ramps. Arriving tourists smiled at their dark, muscled bodies, handsome full-featured faces, the ease with which they lifted things of bulk and weight. Departing tourists took snapshots of them.

“That’s how they see us”, Pono whispered. “Porters, servants. Hula Dancers, clowns. They never see us as we are, complex, ambiguous, inspired humans.”

“Not all haole see us that way…” Jess argued.

Vanya stared at her. “Yes, all Haole and every foreigner who comes here puts us in one of two categories: The malignant stereotype of vicious, drunken, do-nothing kanaka and their loose-hipped, whoring wahine. Or, the benign stereotype of the childlike, tourist-loving, bare-foot, aloha-spirit natives.””

Kiana Davenport: Shark Dialogues (1994)

The captivating history of Hawaii is intricately woven with diverse threads of culture, conflict, and resilience. Today, visitors to Oahu not only have the opportunity to immerse themselves in its natural beauty but also to explore the island’s rich and tumultuous past. Ancient sites of historical and cultural significance include Kaneana Cave, Kukaniloko Birth Site, Healer Stones of Kapaemahu, Kualoa Beach, and Ulupō Heiau. Kaneana Cave has functioned as a site for rituals and religious ceremonies. The cave is named after the Hawaiian deity Kane, representing the god of creation. Thought to mark the genesis of human creation, this cave bears profound cultural significance. The Kukaniloko Birth Site is one of the island’s most significant ancient cultural sites, marked by stones placed where the island’s high chiefs believed the life force of the land was the strongest. Women gave birth to hereditary noble children here, surrounded by fathers and 35 chiefs as witnesses. The 36 stones in the complex symbolize these 36 witnesses. The newborn chief would then be taken to a nearby temple, which was later destroyed to make room for sugarcane and pineapple fields. The Healer Stones of Kapaemahu, four stone boulders located on Waikiki Beach, pay tribute to four legendary mahu. These individuals embodied both male and female traits in mind, heart, and spirit. They brought the healing practices from Tahiti to Hawaii, employing their spiritual abilities to treat diseases. Kualoa Beach attracts large extended-family groups, often gathering here for weekend picnics. In ancient Hawaii, Oahu’s chiefs brought their children to this beach for training to become rulers and to learn about their cultural heritage. The imposing stone platform of the Ulupō Heiau speaks volumes about its cultural significance and the power of its patrons. This ancient Hawaiian temple holds profound spiritual and historical value, serving as a sacred site for worship and ceremonial practices throughout generations.

Historical sites associated with the Kingdom of Hawaii include the Queen Emma Summer Palace, Iolani Palace, and Washington Place. Constructed in the 1840s, the Queen Emma Summer Palace served as a summer retreat for Queen Emma and her husband, Kamehameha IV. Despite its grand name, the building is rather modest and sits amidst expansive gardens, providing a cool oasis enveloped by century-old trees planted by the royal family. Inside, visitors can explore numerous personal belongings of the royal couple, including jewelry, household items, and artifacts reflecting their Hawaiian heritage. Iolani Palace, completed in 1882 during the reign of King Kalākaua, stands as the only royal palace in the United States. It served as the official residence of Hawaii’s final two monarchs and played a central role in the kingdom’s political and social affairs until the monarchy was overthrown in 1893. Queen Liliuokalani endured nine months of imprisonment within its walls. Today, visitors can tour the palace’s grand halls and gain insight into Hawaii’s monarchical history and its tumultuous transition to American rule. Washington Place, dating back to 1846, holds the distinction of being Hawaii’s oldest continually inhabited dwelling. Originally built by John Dominis, Queen Liliuokalani’s father-in-law, it became the queen’s residence following her release from imprisonment. Now serving as a museum dedicated to her legacy, Washington Place commemorates the queen’s life and contributions to Hawaiian history.

Throughout the island, visitors may encounter both historical and active military installations, but one site holds particular significance for all Americans: The Pearl Harbor National Memorial. It stands as a commemoration of the attack that occurred on December 7, 1941. Visitors to the memorial can learn about the events leading up to and following the attack. The USS Arizona Memorial, a sunken battleship, honors the lives lost during the attack. Visitors can take a boat ride to the memorial, observe the remains of the ship, and pay their respects to the servicemen entombed within. Separate and independently managed sites, such as the Battleship Missouri Memorial, Pacific Fleet Submarine Museum, and Pearl Harbor Aviation Museum, offer additional insights into the history of Pearl Harbor. The USS Missouri Battleship, famously known as the Mighty Mo, is where the Japanese surrender documents were signed, effectively ending World War II. Although the surrender ceremony took place in Tokyo, the ship is now part of the museum and memorial complex at Pearl Harbor. The Pacific Fleet Submarine Museum showcases exhibits on submarines and their pivotal role in naval warfare. The museum’s prized exhibit, the USS Bowfin Submarine, offers a glimpse into the life of submariners during World War II. Additionally, the Pearl Harbor Aviation Museum explores the aviation history of Pearl Harbor. The exhibits that tell the story of the attack are displayed within an authentic World War II-era hangar.

The Bishop Museum, Hawaii’s largest museum, is dedicated to researching and preserving the rich history of Hawaii and the broader Pacific region. Established in 1889 with the family heirlooms of Princess Bernice Pauahi, the last royal descendant of Kamehameha the Great, it is the largest museum in Hawaii and houses the world’s largest collection of Polynesian cultural artifacts and natural history specimens. Beyond its extensive collection, the museum serves as an essential educational resource, offering immersive experiences that explore the diverse cultures, traditions, and ecosystems of the Pacific. Visitors to Oahu have the opportunity to explore beyond the tangible relics of Hawaii’s past and immerse themselves in the vibrant traditions of native Hawaiian culture. Through cultural experiences such as lei-making workshops, hula performances, and traditional luaus, visitors can gain a deeper appreciation for the indigenous heritage that persists in modern Hawaii.

Sources

https://www.gohawaii.com

https://www.iolanipalace.org

https://www.bishopmuseum.org